How did being a NEET become an endearing quality in fictional characters?

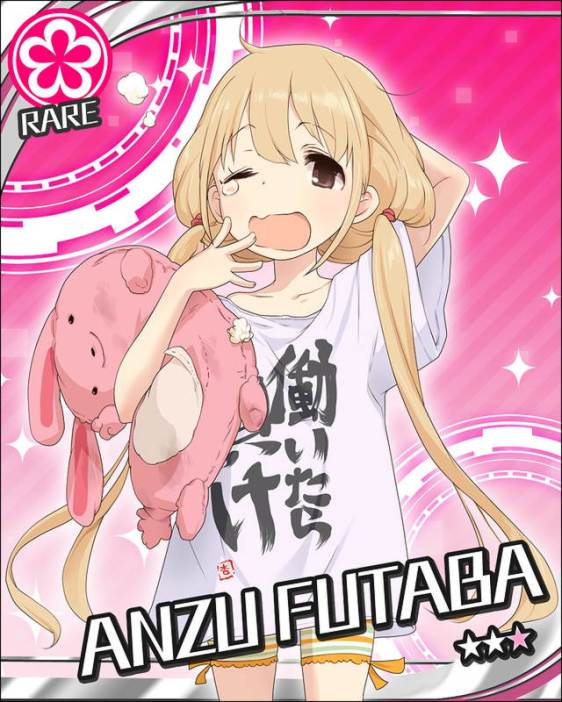

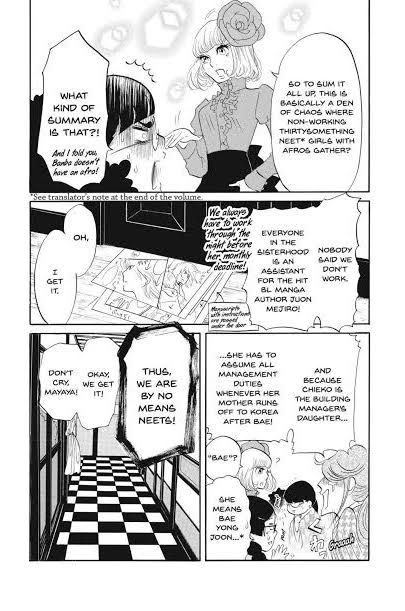

NEET is a term first created in the UK and imported to Japan. Standing for “Not in Employment, Education, or Training,” it’s another way of saying you’re unemployed and probably mooching off of your parents, and most likely somewhere in your 20s to 30s (or beyond). The United States has a similar stereotype in the basement dweller, but whatever the phrasing, it would normally be rather unusual to have such characters be figures of admiration, desire, and more. And yet, this is exactly what we’ve seen out of Japanese media. The geek girls of Princess Jellyfish admit to not having jobs and relying on their folks, but readers connect with them rather than shunning them. Futaba Anzu, one of the characters in THE iDOLM@STER: Cinderella Girls, is not technically a NEET (she has the job of being an idol), but embodies the spirit, being a lazy lay-about whose shirt features the classic slogan of the NEET: “If I work, I lose.”

People don’t necessarily cheer for the forthright and responsible (some would say boring) characters in fiction, but there’s something in particular about embracing the NEET that seems strange on the surface to me, as it’s not exactly an admirable quality in normal contexts. At the same time, there’s a rebellious element, and many have argued that Japan’s economy, rather than the NEETS themselves, are to blame. But the rebellion feels a bit…pathetic, even if possibly admirable.That’s not so much in the sense that NEETS are losers, but it calls to mind the image of an inept geek try their hardest to go camping, only to get lost and fall in a hole. In the end, they’re safe because they can just go back to their home, but within their specific circumstances they’ve tried, even if they end up looking like fools in the process. There’s a tinge of failure, or perhaps fear of failure, and maybe that’s why people connect to them.

One possibility is that a lot of people are or have experienced being NEETS, and it’s probably no coincidence that a character like Anzu would be popular from a mobile game revolving around management of idols. After all, idols are a kind of illusion that fans willingly fall into, and I wouldn’t be surprised if being a NEET inspires the desire to break away from the real world, justified or not. However, one thing that is made clear from Princess Jellyfish and Futaba Anzu is that, at least when it comes to fictional portrayals of NEETS, what defines them first and foremost is passion for something, but most especially passion for the impractical.

Anyone who’s watched anime or read manga for a long time has noticed a kind of reverence for the teenage years, and one factor behind that is the idea that it’s the time in your life when you can truly devote yourself to a task regardless of its practicality. As mentioned by Bamboo on The Anime Now Podcast’s review of Love Live! The School Idol Movie, the difference between an “idol” and a “school idol” in the world of Love Live is that even if you can’t succeed as the former, you can become a beloved school idol through hard work and passion for your beliefs. It’s a safe space away from the realities of a harsh industry. NEET characters, whether they’re older (Princess Jellyfish) or not (Futaba Anzu), appear as if they want to extend this mindset into their later years, fighting against a society that tells them to grow up.

Given the ways in which middle school and high school are framed within Japanese media, it’s maybe no wonder that this happened. It’s supposed to be the prime of your life, the time when your soul burns brightest, and then you’re supposed to quietly file it away or adjust it to how the real world works. Even if it’s arguably socially irresponsible to do that, I think it’s understandable, and maybe this is where NEET characters really draw their power from. They’re characters who hold onto their dreams, but tinged with the colors of reality that contextualize them in ways that don’t turn their impractical aspirations into a pure fantasy.

—

If you liked this post, consider becoming a sponsor of Ogiue Maniax through Patreon. You can get rewards for higher pledges, including a chance to request topics for the blog.

My thoughts about NEETs have largely been colored by Eden of the East, and a bit of Heaven’s Memo Pad. They provoke me to question if, at least in Japanese context, the framing of NEET issue has served to reinforce the ideals of salaryman society. That the main standard of ideal life is making a living through employment, and if you don’t, you’re doing it wrong. Plus, the bundling of “education” and “training” with “employment” seems to suggest that education and training are seen primarily as means to get employment.

Eden’s take on this issue is interesting, since there’s a rebellious attitude towards that standard ideal, but ultimately play it out without having a revolution. There’s a curious optimism at the end of the second film that even without changing the Japanese society as a whole, at least other paths to productivity and making a living outside of conventional employment can have a space to co-exist with the mainstream.

Perhaps I still need to look more into this. But regardless, I still think that Eden of the East’s main idea and greatest contribution is to ask about the NEET question differently. That rather than to accept as given the view of NEETs as problem and asking what is the solution to that problem, it asks what is behind the problematisation of NEETs to begin with anyway, if there’s some ideology underlying that view.

LikeLike

You know, I was actually thinking about something similar, namely how the NEET/Hikikomori as lazy good-for-nothings favors that salaryman society. While the idea of “if I work, I lose” comes across as entitled and irresponsible, I feel like it relates to not wanting to give up one’s individuality, identity, and interests. In that way, I can see it being related to how many women are choosing careers over families because they’re forced into making that decision by Japanese society.

LikeLike

Pingback: Don’t Drill a Hole in Your Head: April ’17 Roundup | The Afictionado

Fundamentally I am a little puzzled with how you can link romantic feelings to your school days to NEET. By definition the two are actually at odds with each other.

Anzu, on paper, is a hard-working idol who does the least amount of work but accomplishes the most given what she does. At 17 years old she bucks the society’s “hard work” mentality and is actually still old enough to be in school. If anything she embodies the professional idol: she is a fake NEET. That is sort of the idealism Anzu paints for me.

LikeLike

Anzu as you said technically isn’t a NEET because she has a career, and she’s younger than the typical NEET range. I think of her more as one example of romanticizing the NEET image than romanticizing school life. However, what leads people themselves to gravitate towards that? That’s the question I was asking and trying to explore.

LikeLike

Just speaking anecdotally, by the early 00s NEET stereotypes that you speak of were not exactly a popular thing yet. The social concerns about the hikkikomori and the term “lost decade” were just becoming something of a publicly recognized thing. I think otaku media has started to address these issues in a more expectant, “hope giving” sort of way, both because it is the kind of escapism that is welcomed and probably the most socially responsible kind of escapism that you could make and still sell well to this crowd. if anything I think the attitude you describe in the post reflects a change in attitude with how people view the young today in Japan. Part of it is that those who suffered through the mid 90s as new graduates are probably at least making life work 20 odd years later, if they’re still watching anime and reading manga.

LikeLike

Pingback: Anikenkai Anime Club 052 - I Will Remember You - Portal Genkidama

Pingback: Anikenkai Anime Club 052 – I Will Remember You – Anikenkai