In the comments section for kransom’s translation of Takekuma Kentaro’s lecture on Miyazaki, a lot of talk is brought up regarding styles and trends according to where the artist is from or where the artist draws their inspiration from. Specifically, the comments center around Miyazaki’s style being similar to that of European artists. Commenter JBR states, “Nausicaa is very similar, in many ways, to the European avant-guard [sic] comics of the 1970’s/80’s, which also emphasize densely-constructed panels and attention to background detail.”

So if the emphasis on European comics is on these “densely-constructed panels and attention to background detail” (something that rings true even for comics that aren’t avantgarde), and the priorities for Japanese story comics is in having the panels be “easy to read” with respect to how panels flow into each other and other aspects, I had to ask myself, “What is the primary feature of American comics, specifically comic books, that makes it stand out?” What, in other words, is the aspect that artists and fans can draw from to make a comic feel very American?

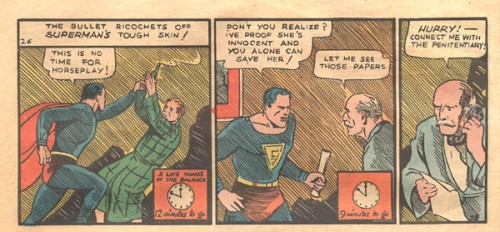

Thinking it over, I’d have to say that I believe that traditionally, the primary feature of American comics is the desire to convey a complete amount of information in a single panel, to really inform the reader that, yes, this is going on right now exactly as you see it. Characters’ poses and actions in relation to text and background all work together to provide a sort of storytelling clarity that some might even regard as overly busy. You know where that foot is going. You know exactly what the characters are doing. You know what is going on in a given scene, as if every panel were an incident in and of itself. Some might say this is the problem with American comics, but I think that wanting to present information in your comic in complete chunks has its merits, in the way radio dramas of yesterday and cd dramas of today do. Of course, I say “traditional” because as comics artists from all over the world interact with each other these differences start to recede, but I think you can still see them in today’s comics.

I’m well aware that there are comics that do not do this, and that even in the comics that do there are plenty of panels which are more for conveying a mood or some other function. I’m also aware that all the visual examples are from superhero comics, and that there’s an entire indie comics scene out there, and famous artists such as Dave Sim, Robert Crumb, Chris Ware, Art Spiegelman, and even Brian Lee O’Malley who do not abide to this “rule” if you can call it one. However, I do feel that this is the aspect of American comics which people remember the most, whether they’re long-time fans or new readers, these panels designed to exist on their own if they have to, but also function as part of a whole.