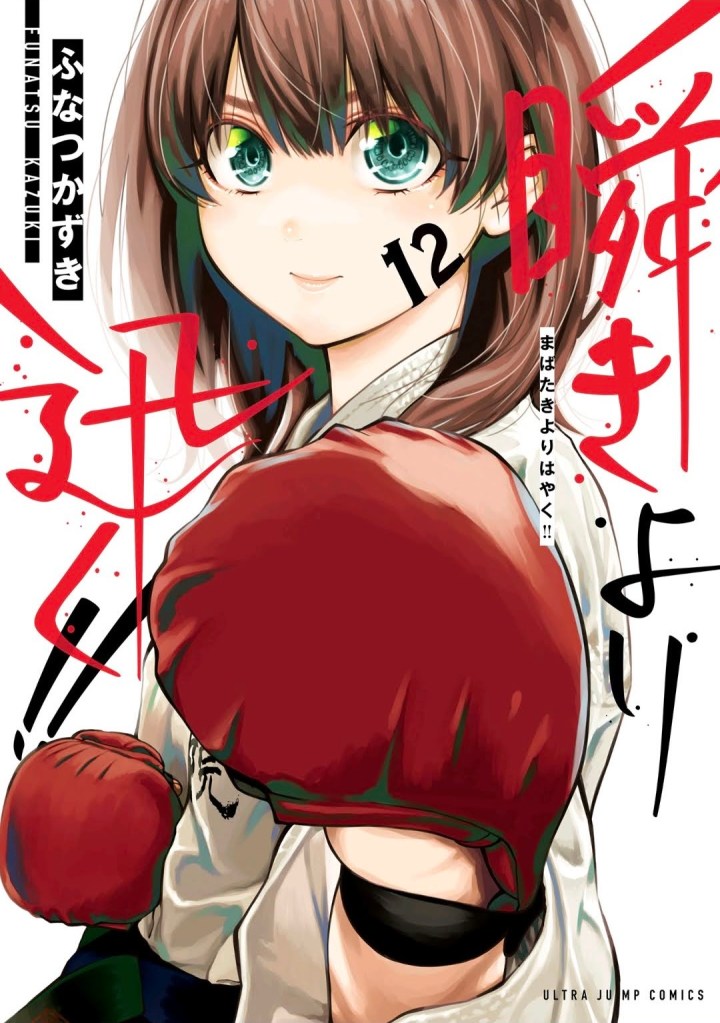

Mabataki Yori Hayaku, the sport karate manga by Funatsu Kazuki, finished in 2025 after 12 volumes. It’s a series that I had been enjoying a great deal thanks to its ensemble of characters at varying skill levels and each with a unique relationship to karate, as well as the solid artwork that communicates the action and intensity of a match on both a physical and a psychological level. While MYH was clearly forced to end a little abruptly, I still think it’s a fun read overall and concludes in a satisfying way.

Kohanai Himari, a clumsy girl who gets inspired to learn karate after being saved by an upperclassman, is the main character of the story. Despite a case of mistaken identity where she confuses two twin sisters raised on karate (one enthusiastic about it and the other cold), Himari joins the school club, which is small and lacking in members. And while she seems ill-suited for any sort of athletics, the more practiced hands realize that she has unusually sharp and perceptive eyes. Soon, she’s practicing daily, growing alongside her teammates, and even gaining a few rivals, all while she and the other characters navigate the various forms of karate-centered drama.

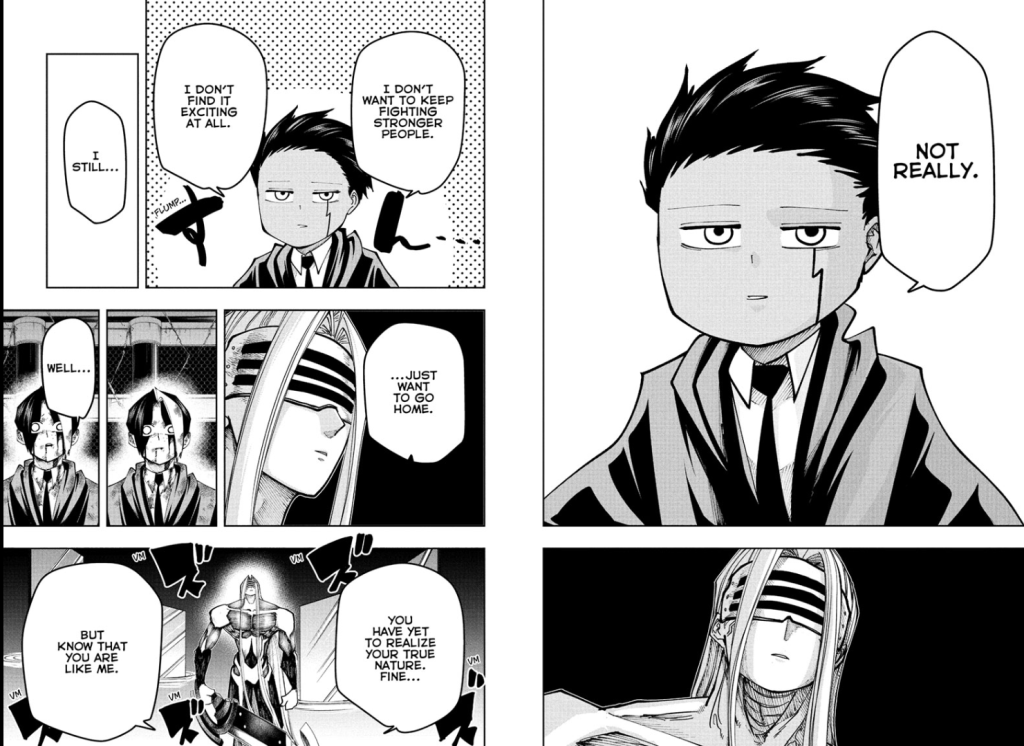

Up until the end, the MYH is very consistent in terms of its sports manga appeal, and everything I wrote about it before still holds true. Seeing Himari come into her own as a competitor is wonderful, and learning the truth about the rift between the twins is satisfying. In the final volume, however, the story suddenly moves at a breakneck pace in order to wrap up everything and move all the characters into their intended positions. The climax of the series happens at a big karate tournament (naturally), and the results are satisfying in terms of the girls’ character arcs. The epilogue then puts them many years into the future to answer the question of “Where are they now?” I really do wish I could have seen the series get there at its normal pace.