Introduction: “Gattai Girls” is a series of posts dedicated to looking at giant robot anime featuring prominent female characters due to their relative rarity within that genre.

Here, “prominent” is primarily defined by two traits. First, the female character has to be either a main character (as opposed to a sidekick or support character), or she has to be in a role which distinguishes her. Second, the female character has to actually pilot a giant robot, preferably the main giant robot of the series she’s in.

For example, Aim for the Top! would qualify because of Noriko (main character, pilots the most important mecha of her show), while Vision of Escaflowne would not, because Hitomi does not engage in any combat despite being a main character, nor would Full Metal Panic! because the most prominent robot pilot, Melissa Mao, is not prominent enough.

—

This is an unusual “Gattai Girls” entry. Sakura Wars is one of Sega’s most beloved video game franchises in Japan, and doing a review/analysis of it based on an animated TV adaptation will inevitably mean I can’t fully capture everything that makes the series what it is. Nevertheless, we have a solid example of an anime that fulfills the criteria of a mecha series with a centrally prominent female pilot, so here we are. As far as I know, the TV series follows much of the same plot, but there are some cases where major events (such as a certain heel turn) do not play out as they did in the game.

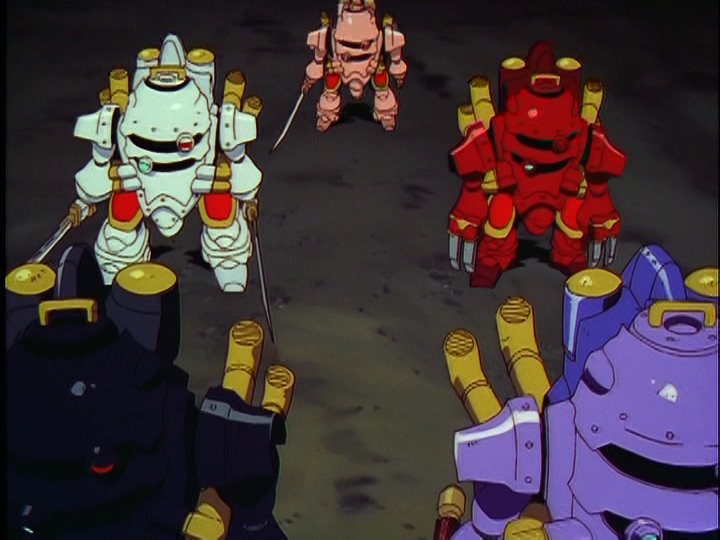

Sakura Wars takes place in an alternate Taisho-era mystical-steampunk Japan where people and technology thrive, but where horrible demonic forces also threaten the peace. The only people capable of fighting them on relatively even terms are the members of the Imperial Combat Revue: a group of girls who have the dual roles of being performers in musicals in the vein of the Takarazuka Revue and fighting as pilots of special spiritually powered mecha known as Kobu.

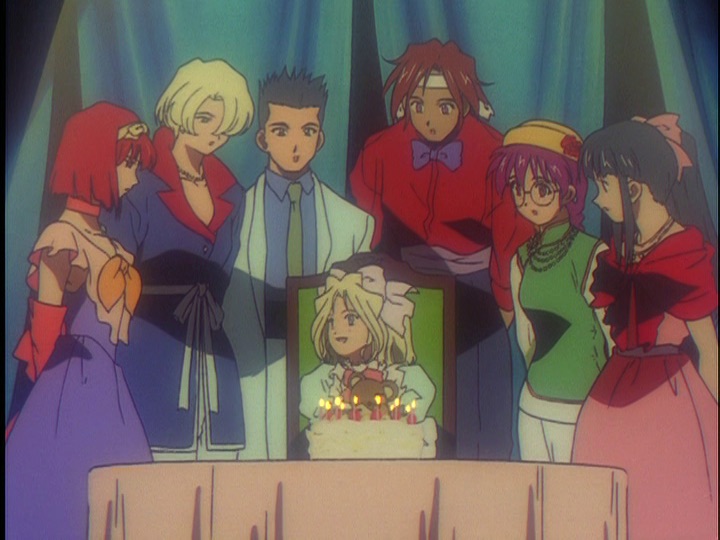

One of the points of appeal of Sakura Wars is that these girls are all interesting and memorable characters, but the face of the franchise is undoubtedly its namesake, Shinguji Sakura. To understand her general popularity, one need only look at Sega’s 60th anniversary popularity poll wherein Sakura got 3rd place behind only Sonic the Hedgehog and Opa-Opa from Fantasy Zone. What makes her so appealing is that she’s essentially the ultimate yamato-nadeshiko—the classical Japanese beauty—but without being a regressive character bound by conservatism.

(SIde note: While I acknowledge that the series is full of excellent female characters, the focus will be on Sakura as the main heroine).

When Sakura first arrives to join the Combat Revue in Tokyo, she’s like a fish out of water. Clad in a kimono, everything about her screams “traditional.” However, this is the Taisho era, a time of increasing embrace of certain Western values (such as marrying for romantic love). Much of Sakura’s growth over the series involves adapting to the cosmopolitan nature of her new environment and her teammates—allies who come from different parts of Japan and the world, and who hold different values—all the while still honing the swordsmanship and spiritual energy that has made her a recruit for the Combat Revue in the first place.

I don’t often devote space to discussing the voices behind the characters in these “Gattai Girls” entries, but I have to make a special exception here because Yokoyama Chisa is simply exceptional. Her voice carries such a range of emotions, from strength to vulnerability, from joy to sorrow, sometimes all at the same time. She’s the main singer in the Sakura Wars opening for this anime (as well as many of the games), and it really does feel like Shinguji Sakura is bringing the song to life.

I understand that romance is actually a significant part of the Sakura Wars games, as the player usually takes the role of a male captain who’s in charge of the squad. In the case of the earliest games and related media, that would be Ogami Ichiro, and I believe Ogami and Sakura are the most popular pairing. However, romance isn’t really a huge factor in the anime, and much of the story is focused on Sakura and the others developing bonds that help them to grow as people and warriors, as well as unraveling the secrets of the demons that are plaguing Japan. In this regard, Sakura is shown to possess immense inner strength, focus, and courage, all of which end up translating to becoming a great Kobu pilot over time.

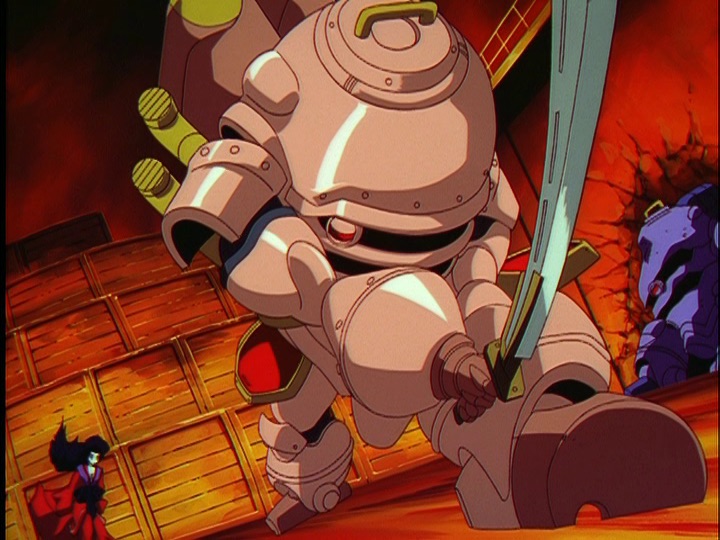

The Kobu themselves look fantastic, their round shapes and steam valves capturing the setting’s aesthetic better than anything else. They’re distinctive, and their unisex designs means that no specific attention is drawn to the Kobu being piloted primarily by girls. Every character fights in their mecha with weapons similar to what they’d use on foot, and Sakura’s is a single katana. The power, will, and resolve to defend the innocent is actually part of Sakura’s appeal as a yamato-nadeshiko, but this is again presented less as a facet of an ossified woman and more an anchor she can use for stability when she needs it.

Shinguji Sakura is the kind of female protagonist who is often imitated but never duplicated. To be able to embody seemingly contradictory values of progress and tradition while truly betraying neither is a juggling act that can fall apart all too easily. She’s the surest sign that just because a character falls under a dominant archetype doesn’t mean they have to be boring or bland.