The moment has come in Kio Shimoku’s Spotted Flower: In the most recent chapter first published in June, the Wife (aka Not-Saki) confronts the Husband (Not-Madarame) about his adulterous actions with Asaka-sensei (Not-Hato). With a rather sparse publication schedule consisting of printer chapters and digital-only supplementals, getting to this point has taken many years. Now that we’re here, though, the confrontation really emphasizes the essence of this thinly disguised Genshiken alternate universe.

The Story Thus Far

A lot has happened since I last posted about Spotted Flower, so I think some brief catchup is in order. Note that I might not remember all details correctly because of how convoluted things have become:

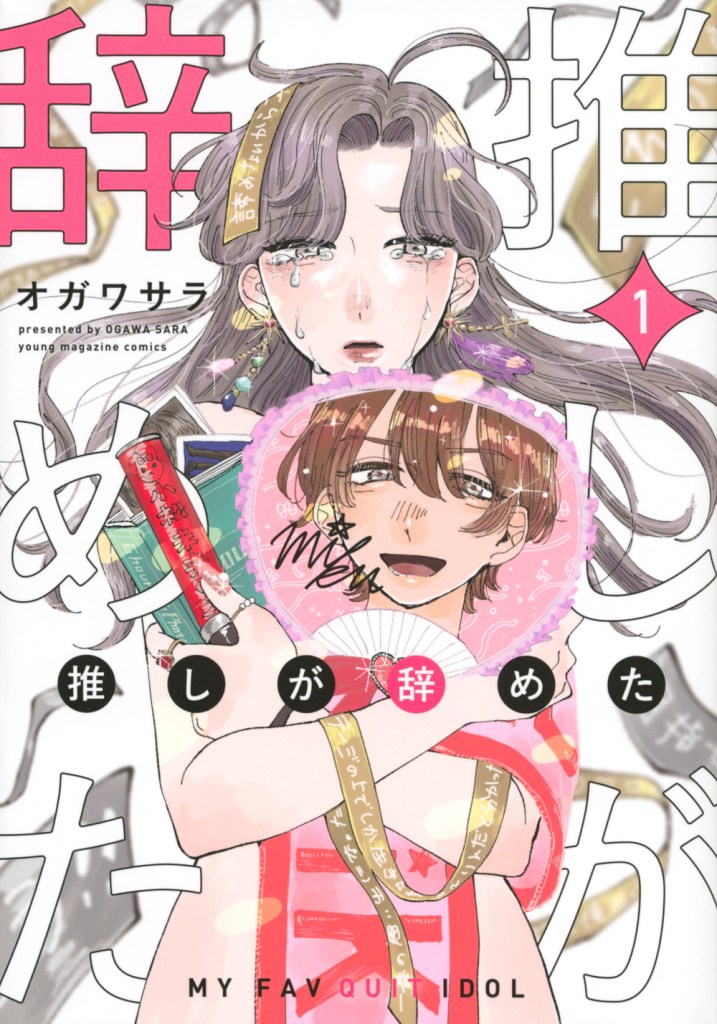

Spotted Flower is about an otaku husband and his normie wife, both of whom were members of the same otaku club in college. At first, the story is about their very different tastes and behaviors, as well as the challenge of having a sex life while she’s pregnant and he suffers from low blood pressure that makes even morning wood difficult to come by. They occasionally meet with and talk with old friends, who are all suspiciously similar to other characters from Genshiken (though they’re not the same).

The Wife eventually gives birth to their daughter, Saki, and one consequence is that the Husband feels inadequate as a partner. Seeing his beautiful wife chatting with her Ex-Boyfriend (Not-Kohsaka), he panics and secretly solicits Asaka-sensei, their old college club junior who once regarded themselves as a crossdressing mane but has since gotten some feminization surgery and whose gender is less clear-cut. The Husband tries to start something, but can’t get it up. No problem, Asaka-sensei declares, and puts their penis up Not-Madarame’s butt.

The Husband is plagued with guilt and shame for cheating on his wife, and Asaka-sensei tries to keep the tryst a secret from everyone they’re close to, including their own partner and manga assistant (aka Not-Yajima). While the two have an open relationship, it’s still big news that Asaka-sensei banged their old senpai. But the truth slowly leaks out little by little, with different people learning at different points from different people. Eventually, the rumor reaches Not-Kohsaka, who decides to look into it on his own.

Of course, the Wife is a sharp and perceptive person, and had naturally suspected that something weird was going on. Eventually, in a moment of weakness, the Wife propositions her ex-boyfriend, but he refuses, despite the fact that he’s actually a serial philanderer. It’s not clear at this point what he’s planning, but we also learn a few things about him as well—namely, that he seems to have hidden feelings for Not-Sasahara, and at one point even kisses Not-Sasahara when he thinks the latter is asleep (He isn’t).

Speaking of Not-Sasahara, his relationship with Ogino-sensei (Not-Ogiue) takes an unexpected turn as she proposes a polygamous marriage between the two of them and her manga assistant (Not-Sue), with whom she already sleeps with. However, this is unlikely to turn into a threesome situation because Not-Sue hates Not-Sasahara for not letting her monopolize Ogino-sensei.

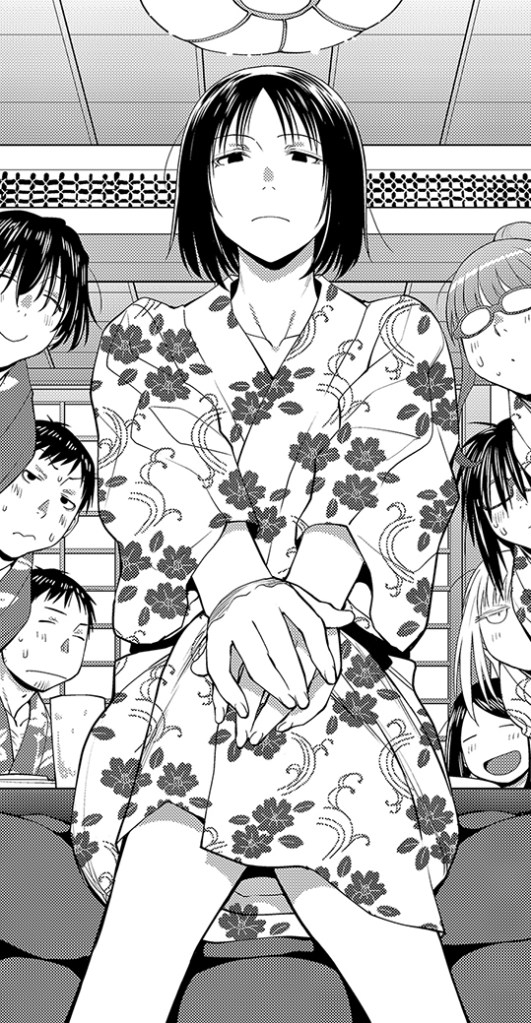

Most recently, the old club members have gathered together for a group getaway. And then, two chapters ago, as the guys and girls are hanging out in gendered groups, Not-Kohsaka casually tells all the boys about what happened between the Husband and Asaka-sensei. Not-Kuchiki, shocked by the news, rushes over to the Wife and blurts it out, asking if it’s true. Here, the Wife herself gets a weighty grin on her face and says, “So it’s finally public knowledge, huh?”

And Now…

That’s where things stand before this latest chapter, which starts with everyone in the same room. The Wife asks if being with her was really that awful, the Husband tries to explain that it’s been great, but that he thinks she’s a goddess residing in a realm on high, and he lives crawling in the mud in the world below. She doesn’t understand what this means, so the Ex-Boyfriend explains that this is an otaku self-consciousness thing. The Ex also explains that he couldn’t possibly be with the Wife because she actually hates his guts—a fact that Not-Saki herself didn’t even remember herself.

The Wife grills the Husband about the whole situation with everyone else (especially the fujoshi) listening intently. As the Wife explains, the guy tends to hide his feelings, so she wants him to be honest. From this, they learn that he couldn’t get hard, but that it actually felt kind of good to be on the receiving end (to the thrill of the fujoshi crew). Not-Saki then goes on about what a weird little otaku club they are: Otaku are supposed to be these innocent and naive people who don’t really know what sex is like, but the people here have sex while cosplaying, engage in threesomes (which Sue adamantly denies), and her own husband got it from behind by a crossdresser. They’ve all had the wrong idea about otaku.

The chapter ends with an ultimatum from the Wife to the Husband: He must get an erection for her, or their marriage is over.

What Does This Mean?

We won’t know what happens with the two of them for another few months, but regardless of how it pans out, there’s a lot to ruminate on already.

I think the biggest revelation from this is the fact that the Wife actually hates her Ex. What has previously come across as a fairly cordial “let’s just be friends” might have been something more serious and dramatic. We know that Not-Kohsaka sleeps around more than everyone else in Spotted Flower, but that a part of him feels empty inside. I had wondered if this was him still taking the break-up poorly, but maybe this behavior from the Ex was already a problem. Or perhaps his unrequited feelings for the Editor were there all along, and he wasn’t honest with himself. Whatever the case may be, I really think it changes the assumed dynamics of the characters, and by extension the story as a whole

I know Spotted Flower is controversial, and that some English-speaking fans of Genshiken have viewed it with derision. While I approach it as a kind of strange alternate universe, the fact that this is the only “new” material is understandably confusing and maybe even frustrating. But the way this latest chapter has played out, I have to wonder if there actually is light at the end of this tunnel for the readers who wanted something a little more wholesome. Granted, the tunnel is still of twists and jagged rocks, and a rock slide might close off the exit, but we’ll just have to see what awaits us.