Volume 7 is the point where Genshiken starts focusing much more heavily on Ogiue’s story, for better or worse (guess which side I’m on!). As the only character at this point who has a powerfully emotional backstory (though I wouldn’t have minded learning about the others in their younger days), it makes sense, even if it pulls the manga away from its more laid-back origins.

What is Return to Genshiken?

Genshiken is an influential manga about otaku, as well as my favorite manga ever and the inspiration for this blog, but it’s been many years since I’ve read the series. I intend to re-read Genshiken with the benefit of hindsight and see how much, if at all, my thoughts on the manga have changed.

Note that, unlike my chapter reviews for the second series, Genshiken Nidaime, I’m going to be looking at this volume by volume, using both English and Japanese versions! I’ll also be spoiling the entirety of Genshiken, both the first series and the sequel, so be warned.

Volume 7 Summary

It’s the dawn of a new age for Genshiken, as Ohno now leads the club. However, an awkward scene with Kuchiki drives away all prospective members, aside from Sasahara’s sister Keiko (who doesn’t even attend the school). This means the balance of the club has shifted to actually have more women than men.

Ogiue’s troubles are only beginning, as she finds out she’s been accepted for Comic Festival. Given her outward hatred of fujoshi, the idea that she’ll be putting out a BL doujinshi frightens her. However, thanks to a pep talk by Ohno, she begins to move forward, though Ohno also uses this as an opportunity to get Ogiue into some mildly skimpy cosplay. Sasahara sees this, and later begins to fantasize about Ogiue, and the other girls in the club (including Keiko!) pick up on the small, yet smoldering sparks between the two.

Ohno and Kasukabe begin plotting to get the two closer, which ends up with her bringing her American friends, Angela Burton and Susanna “Sue” Hopkins, to ComiFes as a way to get Sasahara and Ogiue to be at the event together alone. The two actually begin to hit it off (to the point that it overwhelms Ogiue a little), but a chance encounter with two hometown women from Ogiue’s past—people she hesitantly calls “friends”—clearly induce emotional anguish in her. A confusing moment with Sue at first helps Ogiue calm down, only for her to flash the most hardcore page from Ogiue’s own doujinshi in front of Sasahara—the last person she wanted to show it to.

Sasahara, meanwhile, has his own non-romantic troubles, namely being unable to find work. He’s decided to pursue a career in manga editorial, but keeps getting rejected. Finally, he lands at a dedicated freelance editorial company and uses his experience with Kugayama and Ogiue to finally land a job.

The volume ends with Ohno and Kasukabe setting up a club trip to the resort town of Karuizawa, where they intend to finally get Sasahara and Ogiue together.

Is Kuchiki “Okay?”

Kuchiki’s character is being “that guy”: the one whom the other members barely tolerate because they don’t want to drive out because they either 1) don’t want to get too aggressive 2) have empathy for someone so socially awkward. It’s an understandable situation for anyone who’s had experience with a social circle full of dorks.

Given what’s happened with women and the rising tide against sexual harassment, however, Kuchiki’s character becomes increasingly hard to swallow. It’s not just that he’s got lascivious behavior, and it’s not just that he fails to respect personal space, but that he actively tries to creep on the girls, including attempting to peep on them bathing. Even Nidaime, with its female-centric cast, shows the ladies of Genshiken pretty much enduring Kuchiki’s existence and waiting for him to graduate.

I don’t fault Genshiken for this, simply because it does a good job of reflecting the reality of anime clubs in the 2000s and before. Not only is Kuchiki portrayed as being too spineless to actually threaten them, but it’s not like Genshiken rewards or praises the character. And yet, I have to wonder if a socially conscious series made in 2018 would even let him through the front door, so to speak.

Kuchiki’s not all bad, as he does try to defend Ohno’s cosplay from that one thief, but it’s arguably just an example of having a worse villain make a milder one look better. Sasahara sticking up for him and treating him like a human being does help Kuchiki grow a little bit, but is Sasahara’s kindness accidentally a form of complicity? It’s made more complex by the fact that it’s also one of Sasahara’s best qualities, and what helps him get his editor job. A later chapter in Nidaime has an in-love Ogiue praising this very quality of Sasahara, and even here in Volume 7 you can see her being somewhat smitten by that accepting demeanor. It’s perhaps the fate of the moderate force to sometimes not do enough.

Ogiue’s Right to Love

Volume 7 is where the layers of Ogiue begin to peel away, revealing not just a self-hating fujoshi, but one marred by trauma. The first time I read this volume, it wasn’t entirely clear where it would go, but re-reading while fully aware of Ogiue’s past actually makes it kind of heartbreaking. Her anxieties creep to the surface in many of her interactions, and as her feelings for Sasahara get stronger, it’s clear how much her experiences weigh on her mind.

One of the big moments comes when Ogiue is talking to Ohno about having to make a doujinshi for ComiFes. In it, she directly mentions that she’s drawn doujinshi before, and that she hates herself for being a fujoshi. Looking back, the idea that Ogiue has experience drawing more extreme material only makes sense, but I recall it being a bit of a revelation back when I first read it. This conversation is also the first true indication of Ogiue and Ohno having become friends. Before that, there was still a noticeable amount of animosity between them, and I believe here is where it begins to die down a bit.

Ogiue’s blushing profusely as Sasahara smiles at her is incredibly adorable but also complicated. You can feel the inner turmoil raging inside of her as she questions whether she should be happy. Also, I think her switch from a Haregan [i.e., not-Full Metal Alchemist] doujinshi to a Mugio x Chihiro Kujibiki Unbalance one is an early sign of her secret Sasahara x Madarame drawings.

The Society for the Study of Getting Turned On

There’s something very real and refreshing about the way Genshiken portrays sexual desire. The fact that it’s not limited to the male characters also means Genshiken goes a long way in showing women as beings with sexual desire. The approach isn’t like the hyper-eroticism of a fanservice series or a pornographic title and it doesn’t revel in the lasciviousness of its characters carnal wants, but it also doesn’t shy away from showing their libidos at work in public and private contexts.

Nothing shows this better than when Kasukabe drags Kohsaka off so that they can “do it ten times.” Immediately after, Keiko informs her brother that she’s not staying over that night, and Madarame decides it’s his cue to leave too. Keiko and Madarame, having the hots for Kohsaka and Kasukabe respectively, are clearly thinking similarly about how to “remedy” the situation in private. You can practically feel their hormones being barely contained.

Then the manga cuts to Sasahara playing an erogame while thinking about Ogiue in cosplay. It implies that he’s going the same route as his little sister and Madarame, but the fact that he’s thinking about Ogiue (and not Kasukabe) is significant. The Ogiue cosplay moment happens in the previous chapter, which means Sasahara had Ogiue on his mind the entire time. Let’s also not forget that the guys in the club were willing to use the other girls as masturbatory material, so this shows how much Ogiue’s been encroaching on Sasahara’s psyche. This obviously isn’t the first sign that Sasahara’s into Ogiue, but it certainly is one of the most vivid. Later, when they have a ComiFes planning meeting with Ohno, Sasahara’s brief glances at Ogiue show much his mind’s image of Ogiue still persists.

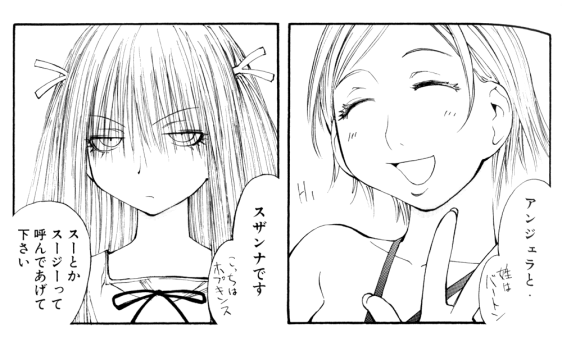

Angela and Sue

As we know from the end of Nidaime, Madarame eventually ends up with Sue. It’s kind of funny that he’s the first guy she meets in Genshiken, as if it was all a long play into the most classic of romance tropes.

I always found Angela and Sue to be fairly realistic, if exaggerated portrayals of American fangirls, but I think that it’s become even more the case as time has passed. Maybe it’s my greater exposure due to social media like Twitter, but Angela’s willingness to just announce her fetishes without hesitation seems not that unusual. Then again, Yoshitake from Nidaime is built from a similar cloth; the only difference is maybe level of sexual experience (Angela is clearly sexually active, while Yoshitake is very much not).

In Volume 7, Sue has a certain grumpiness about her, even as she becomes attached to Ogiue. However, Ogiue is pretty surly herself. I wonder if the softening up of Ogiue leads to Sue becoming less harsh as well.

It’s also funny to think about the fact that, at the time of Genshiken, Sue’s combination of Asuka reference (“Anta baka?”) and Ruri reference (“Baka bakka”) was like, anime nerd knowledge 101. Now, I think it wouldn’t be unusual for the typical fan, Japanese or otherwise, to not have it click immediately.

Final Random Thoughts

The between-chapter specials this volume include Sasahara and Madarame discussing preliminary Kujibiki Unbalance designs. Those drawings are clearly from a younger Kio Shimoku, as it’s the same style as the first chapter of Genshiken! Kio’s aesthetic changes are amusingly visible as a result.

As Sasahara is thinking dirty things about Ogiue, there’s a Gundam model kit box in the background. I think it’s a Sazabi.

In Sasahara’s job interview, he talks about how Kujibiki Unbalance has changed so much since the original cast graduated, to the point that it doesn’t even feel it’s the same series anymore. At the time, it feels like it might have been referencing the graduation of Madarame, Kugayama, and Tanaka, but now it seems to reflect Genshiken Nidaime even more—almost as if Kio doubled down on this idea for the sequel. We know he’s a guy who likes to get referential with his series, but I wonder if Nidaime is even more meta than any of us realized.

The manga Spotted Flower is more than just a story about a male otaku and his non-otaku wife. To fans of the author, Kio Shimoku, the series is also a thinly veiled alternate universe version of his most famous work, Genshiken. With nearly all of the characters in Spotted Flower having direct analogues in Genshiken, the manga is constantly nudging and winking at the audience. Recently, one of those nudges turned into more of an elbow to the solar plexus, and many assumptions about the series have gone out the window. A story seemingly about marital bliss (despite some ups and downs) has become a tale of adultery, and Genshiken fans are left reeling.

The manga Spotted Flower is more than just a story about a male otaku and his non-otaku wife. To fans of the author, Kio Shimoku, the series is also a thinly veiled alternate universe version of his most famous work, Genshiken. With nearly all of the characters in Spotted Flower having direct analogues in Genshiken, the manga is constantly nudging and winking at the audience. Recently, one of those nudges turned into more of an elbow to the solar plexus, and many assumptions about the series have gone out the window. A story seemingly about marital bliss (despite some ups and downs) has become a tale of adultery, and Genshiken fans are left reeling.