Otakon is an event I look forward to every year, and to give you an idea of just how much, I actually plan my time in the US to coincide with it. I went in with the intent of getting some autographs (but not too many as I felt a bit autographed-out from my Anime Expo experience), but ironically I pretty much got everyone but the three I was looking to get the most: Hirano Aya, Nanri Yuuka, and Kakihara Tetsuya. Though a bit disappointed as a result, I realized that this is Otakon and it’s always impossible to accomplish everything you want to do. The scheduling is so jam-packed with events that time is always against you, but then you look back and see all of the fun you had.

This year, as seems to be the case over the past few Otakons, Baltimore was hot. Given that most of it is spent inside an air-conditioned space this isn’t so bad, but there always came a time where people had to brave the heat. Taking Megabus to Baltimore, for example, requires one to walk quite a distance to catch the local city bus. It’s a trek I’m accustomed to at this point, but still one I have to brace for. As for the people in elaborate cosplay, you have my pity to an extent, but seriously you guys must have been dying, especially the full-on fur suit wearers.

Industry Panels

Urobuchi Gen

When it comes to industry guests, my main priority is generally the Q&A sessions followed by autographs, and the reason is that I love to see people pick their brains, especially the creators. I always try to think of a good, solid question or two to ask them, and over time I think I’ve become pretty good at it, because the responses I receive are generally great, though actual credit for the answers of course goes to the guests themselves.

The first industry panel I attended was that of Urobuchi Gen, writer of Fate/Zero and Puella Magi Madoka Magica, two shows which are the new hotness, and by extension make the man himself the new hotness as well. Surprisingly, there was only one question nitpicking continuity, and the rest were about his work, and even some “what if” questions. From it, we learned that Urobuchi is inherently suspicious and so would never sign a magical girl contract, considers Itano Ichirou (of Itano Circus fame) to be his mentor, that he would never pick Gilgamesh as his servant, that the main reason Kajiura Yuki did the music was because of SHAFT Producer Iwakami’s magic, and that working with both UFO Table and Shaft is like being aboard the USS Enterprise and meeting different alien species. In addition, it turns out that Madoka Magica wasn’t influenced by any magical girl series in particular, and the closest lineage it has is with Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha (atypical magical girl show with striking and violent imagery) and Le Portrait de Petit Cossette (a gothic-style show by Shinbo). Given my recent post about this topic, I have a few words in response to that, but I’ll save it for another post.

As for my question, I asked Urobuchi how he felt about influencing such an enormous industry veteran in Koike Kazuo (who is in the middle of creating his own magical girl series), to which he answered that he considers it something he’s most proud of. Though the two have not talked since that interview, he still follows Koike on Twitter. Later, I would get a Madoka poster signed by him.

Satelight

I also attended the Satelight (Aquarion, Macross Frontier) panel, attended by Tenjin Hidetaka (who technically isn’t a Satelight employee), which was just a fun introduction to their studio. They explored their history, from making the first full-CG television anime (Bit the Cupid), the creation of some of their less-regarded shows (KissDum, Basquash!), and into the modern age. Given the small attendance it actually felt a bit personal, and in this time we had some pretty interesting facts dropped on us. A studio which prefers to do original animation instead of adapations, we learned that they sometimes just like to animate things because they can. Case in point, they showed us Basquash! footage they animated just because they liked the characters and world so much, with no additional TV series planned for it. About director and mecha designer Kawamori Shouji, we learned that he likes to work on 3-5 projects simultaneously despite his somewhat old age (52), that Kawamori is devoted to making anime look good, sometimes at the expense of his budget.

They also showed us some CG-animated clips of concerts by Ranka Lee and Sheryl Nome from Macross Frontier, which were really nice and elaborate. Originally they were meant to be used in commercials for a Macross Frontier pachinko machine, but the 3/11 earthquake prevented the commercial from going on air. Another Satelight anime they showed was the anime AKB0048, which actually looks amazing, and from all reports by even the most cynical of reviewers, actually is. Kawamori even graced us with his recorded presence, giving an interview where he briefly discussed topics such as attending Otakon years ago and making the second season of AKB0048.

Given the flow of conversation, when it came to the Q&A portion there was one question I just had to ask: Why did Kawamori end up directing a show like Anyamaru Detectives Kiruminzoo, a show about girls who turn into animal mascot characters and solve mysteries, an anime seemingly far-removed from his usual mecha and idol work? The Satelight representative’s response was, Kawamori is known for working on anime with transforming robots, and when you think about it, transforming animals are not that different from transforming robots. Hearing this, I actually had to hold back my laughter.

One last thing to mention about the Satelight panel was that the laptop they were using was on battery power, and when it started to run out of steam, rather than finding an AC adapter to plug into a wall, they actually just gave the industry speaker another laptop entirely, also on battery power. An amusing hiccup in an otherwise great panel.

Maruyama Masao

Maruyama Masao is a frequent guest of Otakon. One of the founders of Studio Madhouse, he’s been to Baltimore for many, many Otakons, and it had gotten to the point where I began to feel that I could skip his panels to see other guests. This year was different, though. First, with the unfortunate death of Ishiguro Noboru, the director of Macross and Legend of the Galactic Heroes who had died just this past year, it made me realize that the 70+ Maruyama won’t be around forever. Second, this year Maruyama actually left Madhouse to form a new studio, MAPPA, an unthinkable move for someone in as good a position as he was. The studio was created in order to obtain funding for Kon Satoshi’s final project, The Dream Machine, but in the mean-time it also released its first television anime, Kids on the Slope. Even if Hirano Aya’s autograph session was originally scheduled for that time (it got moved), I felt I had to attend Maruyama’s Q&A. In fact, if you are ever at Otakon, I highly suggest anyone, even people who think they might not be interested in the creative side of anime, to attend one of his panels. His answers are always so rich with detail and history given his 40-year experience that you’re bound to learn something and then thirst for more knowledge.

Some of the highlights include the fact that he’d very much like to make an anime based on Urasawa Naoki’s Pluto but thinks the right format, eight hour-long episodes, would be difficult to fund (the manga itself is eight volumes), that half of the animation budget of Kids on the Slope went to animating the music performances, and that he is looking to try and get funding for Kon’s film in the next five years. I find it personally amazing that he would think of the format best-suited for Pluto first, instead of thinking how the series would fit the typical half-hour TV format. In addition, Maruyama pointed out that a lot of work was done in Kids on the Slope to blend and hide the CG, and I think it shows.

In any case, while I would normally be content to just give a summary of the panel, I’m going to link to a transcript just so that you can read the entire thing. The question I asked is as follows:

How did director Watanabe Shinichirou (director of Cowboy Bebop and Samurai Champloo) become involved with Kids on the Slope?

“I was working with Watanabe from back in the MADHOUSE days. Unfortunately there were about three years where nobody got to see his work — his projects always got stopped at the planning stages. So when I got Kids on the Slope, I handed him the manga and said, ‘here. You’re doing this.’ At MADHOUSE we had developed a feature — it was already scripted and ready to go, but then I left the company and the project fell through, so I gave him this as something to do. I really think he’s one of the top directors in Japan, one of the top 5. That’s why I wanted to create a theatrical animation with him. Up until this project, he’d only worked on original projects, so this was his first adaptation from a manga, and as a result, he didn’t really know how faithful he had to be, or if he had room to adapt, so he put up a lot of resistance at first.

“Mr. Watanabe loves music, and has a lot of deep thoughts on the music. So I told him that it was a jazz anime, and that he was likely the only director that could pull it off. That convinced him. Then Yoko Kanno said, ‘if Watanabe is working on this, I’d like to work on it too,’ and so that’s how that show came to be.”

Also note that in the photo above, Maruyama is wearing a shirt drawn by CLAMP to celebrate his 70th birthday, showing him to be a wise hermit.

Hirano Aya Concert

Partly because of scheduling conflicts, I attended the Hirano Aya concert knowing that it would be my only experience getting to see her. As expected, it was quite a good concert, and I had to get up despite my con fatigue for “God Knows,” but there wasn’t quite this process where I felt won over like I had with LiSA at Anime Expo. Thinking about it, it’s probably because I’m already familiar with Hirano Aya’s work.

I did wonder if her cute outfit was designed to kind of draw some of the controversy away from her, the large bow tie on her head possibly trying to restore her image in the eyes of certain fans. At the same time, given her songs and given her vocal range, I had to wonder if she would benefit from being presented as less of an “idol” and more of a “singer.”

Getting to the concert 15 minutes late on account of 1) the Baltimore Convention Center not being entirely clear as to what can lead to where, and 2) my own forgetfulness from not having done this for a year, I sadly missed the announcement that she would be signing autographs at the end, and ducked out after the encore was over. Alas, I’ll have to wait a while before I get the chance to have my volume of Zettai Karen Children signed.

Other

Apparently Opening ceremonies was ushered in by the Ice Cold Water Guy. Unfortunately I wasn’t there, but I heard it got quite a reaction.

I also attended (the last half of) the Vertical Inc. panel, whose big, big license is Gundam: The Origin. Honestly, I’d never expected to actually see it released in the US, seeing as Gundam is practically seen as poisonous in the States, and I doubly didn’t expect it from Vertical. In addition, though I didn’t attend, some friends went to the Kodansha Comics panel and got me a Genshiken poster! Would you believe that I’ve never owned a Genshiken poster? This one even has Ogiue on it! Granted, I can’t put it up just yet, but it’s basically a copy of the English cover to Volume 10.

Also, while I didn’t attend some of the guest Q&As, I did conduct personal interviews with some of them.

Fan Panels

New Anime for Older Fans

A panel run by the Reverse Thieves, I was happy to see that the room was so packed that people were starting to get turned away at the door. The goal of the panel is exactly in the name: the two panelists pointed out anime that have come out within the past five years that they felt older anime watchers, even the kind who have children of their own, could enjoy. By far the most popular show was The Daily Lives of High School Boys, which just got endless laughs. What I found to be really interesting though is that I could tell the panel was working because I heard more than one baby crying throughout the whole thing. Assuming that the babies did not magically crawl in on there own, I could only assume one or more parent was there with them, also learning about New Anime. I even had a couple of old college friends attending Otakon tell me how much they wanted to watch some of these shows.

Genshiken: The Next Generation

If anyone thought this was my panel, my apologies! It was actually run by my old Ogiue co-panelist, Viga, and offered an introduction for existing fans of Genshiken to its sequel, Genshiken Nidaime aka Genshiken: Second Season. Overall, I thought it was a fine panel, though at points I felt like Viga couldn’t quite decide who the panel should be for, explaining some things while omitting other details entirely. Should it assume that people had read the current chapters or not? If the panel could have a tighter focus with a clearer idea of where it wants to go, I think it would be much better.

Fandom & Criticism

This panel was dedicated to introducing and exploring the concept of “active viewing” to a convention audience, which is to say the idea of distancing oneself from one’s own emotions while watching something in order to more accurately gauge what the work is saying. Hosted by Clarissa from Anime World Order, as well as Evan and Andrew from Ani-Gamers, I took interest in the panel partly because I know the panelists, but also because as an academic myself the concept comes into play with my own studies. The discussion was quite fruitful I think, though one thing I do want to say is that I feel the concept of distancing and dividing between the rational mind and how one’s emotions operate while consuming media can make it difficult to see how other people might view a certain show, and that it is important, I feel, to consider emotions and “passive feelings” while watching a show, as they can shape one’s experience in a way that “active viewing” may tend to break down like a puzzle.

Anime’s Craziest Deaths

It was my second time seeing Daryl Surat’s violence smorgasboard of a panel, and probably what impressed me the most wasn’t any single clip, but the fact that the footage was (as far as I remember) 100% new compared to last year’s Otakon, and that a lot of it came from newer shows. The panel is a treat to watch, and that the craziness of a death doesn’t necessarily have to do with its violence level, but it certainly helps. The panel was a full two hours, so the middle felt like it started to drag, but I think it has to do with the basic idea that people’s attentions will slowly fade over time, so it’s somewhat necessary to up the ante as it goes along. I’ll finish this part by letting Daryl himself offer some sage advice.

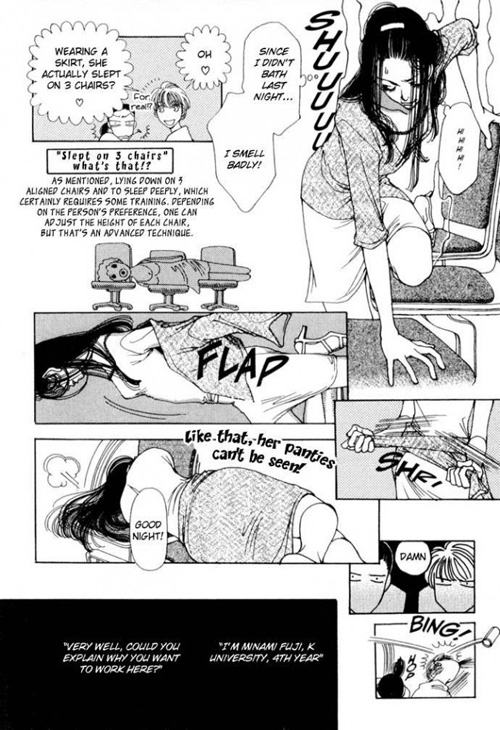

The Art of Fanservice

The last fan panel I attended was hosted by the third host of Anime World Order, Gerald, and it was a brief look through the history of fanservice, as well as some of the general differences between fanservice for men and fanservice for women. Defining the art of fanservice as titillation which is not just outright pornography, Gerald’s theory, which seemed confirmed by the audience’s reaction, was that fanservice for guys is typically very visual, very isolated, while women usually require some kind of context. A pair of bare breasts, no matter what situation the woman is in, can be enough for a guy, but a girl usually wants some backstory. Possibly for this reason, the clips of women’s fanservice tended to be a little longer. Also of interest was the Cutie Honey Flash opening, which was a Cutie Honey show targeted towards girls, and though Honey is still leggy and busty, I noted that the way the shots are framed is a far cry from its most immediate predecessor, New Cutie Honey.

I think the idea of “context” does definitely ring true to an extent, but I have to wonder about the degree to which people, especially otaku, defy those gendered conventions. For example, there is definitely “context-less” fanservice in Saki, but there are also moments which are meant to thrill based on the exact circumstances of the characters’ relationships, like when Yumi tries to recruit Stealth Momo for the mahjong club and shouts, “I need you!

Speaking of Saki, why I had a panel to present this year as well.

Mahjong

It was likely thanks to Saki: Episode of Side A that Dave and I got the chance to once again present”Riichi! Mahjong, Anime, and You.” The format was essentially the same as our panel from 2010, where we try to help the attendees learn not so much how to play mahjong (an endeavor which requires hours and hours of workshop time), but how to watch mahjong anime. New to 2012 though were the fact that we had two years of additional playing experience, which meant we knew what we were talking about a bit more, as well as a number of new video clips to thrill the audience, including one that Dave was so excited about he was almost willing to skip the order of presentation just to reveal it).

It was held in a larger room than last time, and though there were still some empty seats, the fact that we were able to mostly fill a room at 10 in the morning on Friday pleased me so.

After the panel, I was waiting on line for the Urobuchi panel, when the people in front of me not only recognized me from the panel, but also let me join in a game of card-based mahjong, where instead of tiles playing cards with the images of tiles are used. From this I learned that mahjong cards don’t work terribly well because it becomes extremely difficult to see your entire hand, but I have to thank those folks anyway for giving me the chance to play, and though the cards are less than ideal, they’re still handy in a pinch, especially because carrying tiles takes so much more effort.

Thanks to Dave’s effort, however, we actually brought tiles with us to play, and on Friday and Saturday, Dave and I managed to find time to sit down and play for a few hours against not only opponents we already knew but also people we’d never seen before. The tables at the conference weren’t particularly suited for this, and we had to find a table edge and play the game with the mahjong mat angled diagonally. I ended up doing pretty well overall, including an amazing game where I never won or lost a hand and maintained a default score of 25,000, but what really stood out to me is the realization that we had all improved since we started playing mahjong. I know I said it before in discussing the panel part, but playing live against other people made it so that even my mistakes were the mistakes of a more experienced person who could learn from them.

Apparently we weren’t the only ones doing this, as we saw a second mahjong group as well. I couldn’t stay long enough to assess their ability, but as long as they were having fun it’s all good.

Other Photos (mostly cosplay)

Despite a number of good costumes out there, I actually didn’t take too many photos this year. I blame the amount of times I had to hurry to get to the next thing on the schedule. Also, I saw absolutely no Eureka Seven AO cosplay. Promise me for next year!

This was actually the first Fuura Kafuka cosplayer I had ever seen, and I’m amazed (and grateful) that someone would remember her. A funny story came out of this, as the cosplayer had not been aware that Nonaka Ai (Kafuka’s voice actor) was at the event. I told her about the autograph-signing on Sunday, and I hoped she was able to make it. Now, onto the next.

Overall

While at the convention I would notice little things here and there that I thought could use some improvement, the sheer amount of content at Otakon means that with even a few days of post-con recovery the bad mostly recedes away and all that I’m left with is fond memories. One complaint I do have, however, is that because the convention is set up to have some entrances and pathways usable and some off-limits, it is extremely difficult to tell just based on the map given in the con guide how to get from location to location. As an Otakon veteran at this point, I mostly have no issue with it, but even I ran into problems while trying to find the Hirano Aya concert. A combination of better signage to point people to the right locations alongside a clearer map would do wonders.

Even though Otakon had a “cooking” theme this year, I didn’t really feel it, pretty much because I didn’t attend any of those related events. At this point, every Otakon is starting to feel similar, but I can never hold that against it. After all, with a convention this big and with this much to do, I feel that we as fans of anime and manga make of the convention what we want. This isn’t to say that the way the convention is run doesn’t matter, of course, but that it is run smoothly enough that it becomes almost unnoticeable.

Truth be told, I used to take the sheer variety of panel programming and activities at Otakon for granted, but when I attended AX for the first time this year, I realized how limited that event is by comparison. Not only are there a good amount of industry panels with all of the guests they’ve flown over from Japan (or elsewhere), but the fan panels are a nice combination of workshops, introductions, and even philosophical explorations of topics concerning fans. Seeing Otakon once more in person, I knew this was indeed the con I waited for all year.