At this point, Otakon is a given in my life. I have enough faith in the people who run the anime convention every summer that they will create a rewarding experience. But short of anything pertaining to Genshiken, Otakon 2023 ended up with a guest announcement straight out of my otaku wishlist: Iwao Junko, the voice of Daidouji Tomoyo in Cardcaptor Sakura.

And yet, somehow, Iwao was only the tip of the iceberg. Between Asamiya Kia (manga artist of Silent Mobius, Nadesico), Aramaki Shinji (mecha designer on Bubblegum Crisis, Magazine 23), Terada Takanobu (producer on Super Robot Wars), and even the sleeper hit that was Ikezawa Haruna (science fiction writer and the voice of Yoshino in Maria Watches Over Us), I feel like I three conventions’ worth of experiences.

Line Con No More

Otakon 2023 took place from July 28 to July 30, once again at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC. It was coming off a previous year with record-breaking attendance, and two big questions were whether 2022 was a fluke caused in part by the US opening up again after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and how Otakon would handle the flow of foot traffic if it wasn’t. Long story short: Otakon actually surpassed its record this year, and the lines got noticeably better. While there were still a few hiccups here and there (like an unusually long wait to get my panelist badge due to a change in how they handled that process), it’s no coincidence that multiple people in the post-con feedback session praised the staff for fixing most of the congestion issues in a single year.

Fixing the lines was of even more paramount importance due to the weather over that weekend. DC was blisteringly hot; including humidity, there were times the temperature was reported as feeling like 112 degrees. Otakon needed to make sure people could get into that convention center quickly and easily, and they succeeded.

Lack of Masking Policy

I know it is incredibly difficult to put the genie back in the bottle, especially because “officially” COVID-19 is no longer a national emergency, but I really do wish Otakon would re-implement a mandatory masking policy. While I didn’t catch it at this convention, I was definitely in circles where the virus was present, and it would just allow more people to attend the con.

Industry

The guest list this year was truly packed, to the extent that I had to make some serious decisions as to what to spend time pursuing. Kawamori Shoji (creator of Macross) would have been near the top of the list any other year, but the fact that I had already gotten the chance to interview him in 2018 meant sacrifices had to be made. There were also a great number of manhwa artists at Otakon 2023, and as a general enjoyer of comics who is less familiar with Korean comics, this could have been a great opportunity to learn more. Alas, time was truly limited.

A good chunk of my time this year was thus spent on obtaining autographs because a lot of the guests are industry veterans, and some are getting up there in age. It may sound a bit morbid, but I’m worried that we’re going to lose more and more great figures in anime and manga, and I want the chance to see them and thank them before it’s too late. At the same time, I do worry that too much of my Otakon experience ends up being in autograph lines, and every year is a bit of a struggle in that for every wonderful thing you do, you know you’ll miss at least two other equally fantastic experiences.

Iwao Junko

One guest panel highlight for me was Iwao Junko’s, where she went over how she got into voice acting, her earliest days in the industry, and how she eventually made it into a full-time job. I have a detailed summary of the panel as its own post, and I also interviewed Iwao alongside her frequent music collaboration partner, Kawamura Ryu.

Mecha Guests

Another panel I was looking forward to featured multiple creators involved with mecha, including all the ones mentioned in the introduction. Just getting to hear them banter back and forth was entertaining, and you could tell that all of them would gladly talk your ear off if given the chance. One funny part of all this is the fact that Kawamori was clearly but somewhat surreptitiously drawing on his tablet in between answering questions—a fact that one panel attendee humorously called him out on (it turns out he was working on a project).

I got to sit down with two of the guests and talk more in depth: mecha designer Aramaki Shinji and Super Robot Wars producer Terada Takanobu.

Ikezawa Haruna

But there was one guest who was possibly the sleeper hit of the entire con: Ikezawa Haruna. While Ikezawa did her requisite panel about what it’s like to be a voice actor, she also did something incredibly rare for Japanese guests: run a panel entirely about one of her own personal interests.

In this case, it was a panel all about Japanese SF as compared to Western SF. Not long after she started, it was crystal clear that her knowledge was encyclopedic, and that her passion for the subject was through the roof. She probably knew more about science fiction in that room than the entire audience combined, and she made some interesting points about the essence of regional science fiction. For example, in the context of Japanese SF, she mentioned how xenophobia has become a big topic because it’s a major subject right now in Japanese society.

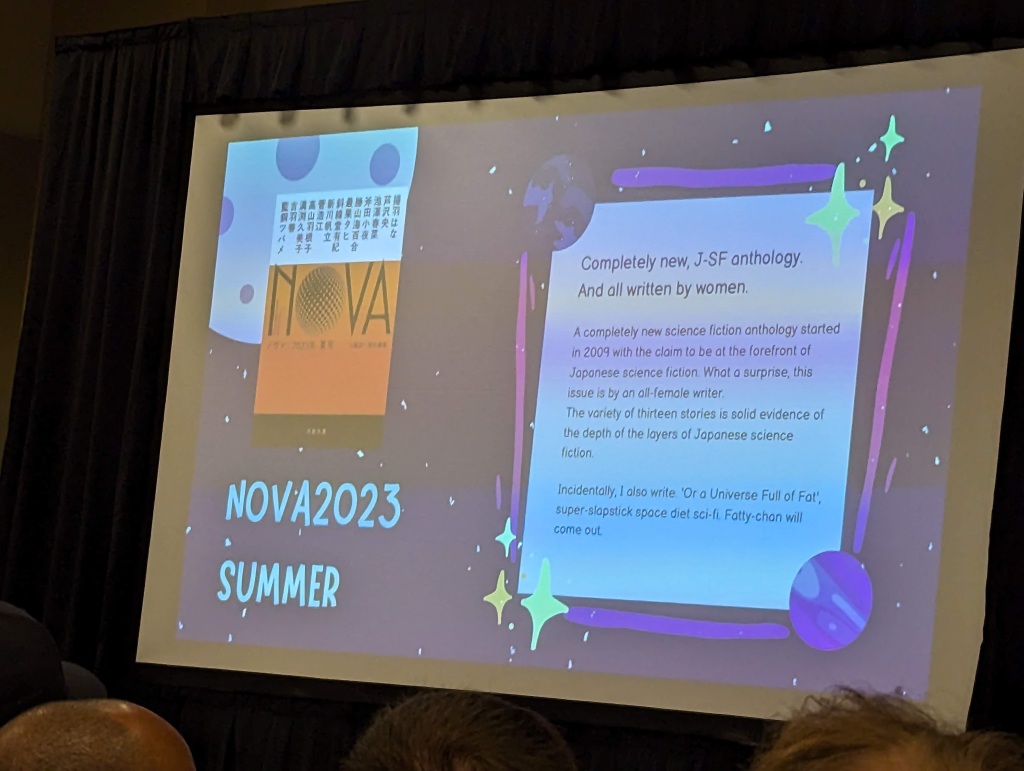

Ikezawa talked about how she actually prefers the term SF to “science fiction” because she thinks Japanese SF encompasses so much more—the abbreviation can stand for sukoshi fushigi (“a little mysterious”), speculative fiction, super fantasy, and so on. She also gave a variety of recommendations, including stories she’s written herself. These are Nova 2023 (an all-woman anthology), SF in 2084 (an anthology themed around stories that take place in 2084), the Naoki Prize–winning Maps and Fists by Ogawa Satoshi, Law Abiding Beast by Harukure Kouichi, and First, Let the Cow Be the Ball by Isukari Yuba. Unfortunately, all of them are in Japanese, but another story by Isukari, Yokohama Station SF is available in English.

Anime Screenings

While I was unable to attend the Discotek panel this year, I do think it’s worth mentioning the fact that they licensed all the Digimon Adventure movies, including both the original Japanese versions as well as the smashed-together film shown in US theaters. Not only is this the first time they’re all available in English, but Discotek did a special screening of them at Otakon. Sadly, I couldn’t attend that either, nor the showing of Macross Frontier: The False Songstress. That’s because I chose to watch the US premiere of The Tunnel to Summer, the Exit of Goodbyes, which I’ve reviewed here.

VTuber Presence

While there were cosplayers and artists who were repping the VTubers, there wasn’t much of an official presence (in contrast to Anime Expo, where it was a major force). That said, the group Phase Connect had a booth. I visited and bought an acrylic stand of Dizzy Dokuro.

Panels

Due to everything else going on, I shamefully ended up not attending very many fan panels this year despite that being one of Otakon’s best features. And for the ones I did, I could only see them in part.

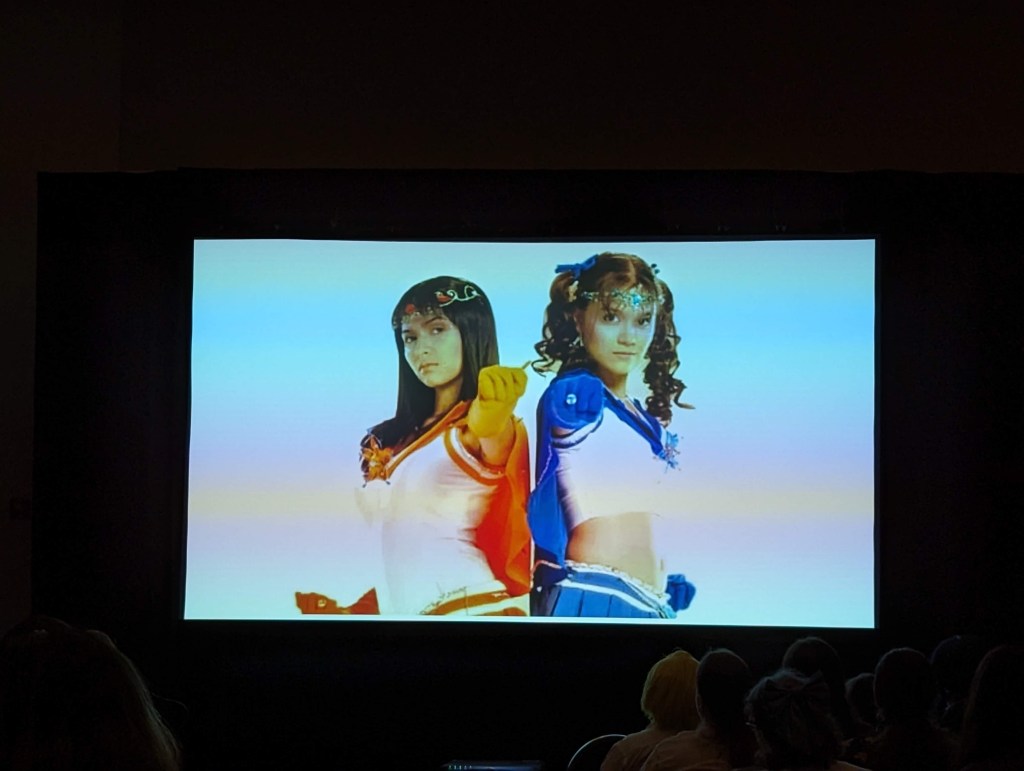

I do want to give a shout-out to Anime in the Philippines, as it definitely taught me new things, and gave a window into a culture and fandom that I was largely unfamiliar with. For example, now I know that Mechander Robo aired there, and I learned about this:

I did present on two panels this year myself, though: “Giant Train Robots of Anime and More” and “Densha Otoko: Train Man, Modern Myth, Internet Legend.” The theme of Otakon 2023 was trains, so I decided to play along.

Giant Train Robots was a joint project between myself and Patz from The Cockpit. We both love mecha, and I also relied on his greater knowledge of the tokusatsu side in bringing this together, and I think the result was a fun and breezy panel whose goal was to entertain, inform, and leave the audience appreciating trains that turn into robots. We got a good-sized attendance despite being at 1030am on Friday, and I hope everyone enjoyed it.

The Densha Otoko panel was all me, and I had actually started thinking about doing it since the end of Otakon 2022 when they had announced the train motif for the following year. Densha Otoko had been such a phenomenon in the mid-2000s, and I was curious to both look back on that era and to see what was its legacy today. I seemed to get mostly people who had already seen or knew about it, but that was just fine with me.

I think Giant Train Robots actually got more attendance than Densha Otoko, and I find that interesting because it used to be that the evening panels were better attended than the morning ones, and that mecha panels weren’t terribly popular, at least back in Baltimore. And this is on top of us actually being at the same time as a different giant robot panel! I wonder if there has been a generational shift or something that would explain this.

Food

After many years, the convention center cafeteria was finally open, giving another option for those who want to get something to eat but don’t want to travel too far. I dropped in there once, and saw that there were three options: Japanese, pizza, and hot dogs/sausages. I went for the last option (which was pretty similar to what’s offered at Ben’s Chili Bowl) mainly because it had the shortest kind, and it was pretty decent. The Japanese food naturally had the longest line at an anime con, though I still remember Otakon staff claiming a long while back that the sushi was actually pretty decent.

But the best food in the Walter E. Washington Convention Center was still the Caribbean food stand, which was located at the far end of the Exhibit Hall. While all con food is inevitably overpriced, this place always feels like the best deal, and the meals feel well balanced in terms of taste and nutrition. I’ve had something from them pretty much every year, and they never disappoint.

Cosplay

Closing Thoughts

2023 was definitely a strong Otakon in spite of circumstantial issues like the weather. Most importantly, I got to meet Tomoyo.

That said, the amazing thing is that next year promises to be even bigger and more powerful because it’ll be Otakon’s 30th anniversary. I’m already brainstorming ideas for panels, and wildly speculating on potential guests. I feel like it would be the perfect time to get people who were big back in 1994, and I trust the staff running the show to bring in some big guns.