What if there was a sequel to Journey to the West, the story of Sun Wukong the Monkey King, and it was set in the near future? And what if all the characters were Lego people? That’s the basic premise of Lego Monkie Kid, an Asia-focused media franchise featuring toys, a cartoon, and more. I first noticed Monkie Kid thanks to clips on YouTube, and found myself impressed by the surprising quality of its animation. I recently got the chance to watch the actual series, and find it to be a kids show that, while modern, is also reminiscent of action cartoons from decades past.

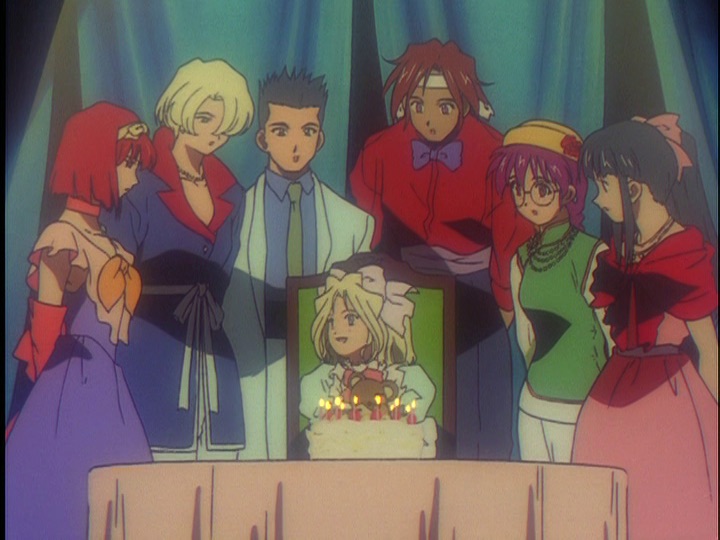

The premise of Monkie Kid is that a noodle delivery boy named MK discovers the legendary staff of the Monkey King and becomes his successor. Now, he must fight against the now-freed Demon Bull King, who was originally imprisoned by Wukong himself, with the help of a close group of friends.

One of the first works that Monkie Kid reminded me of was American Dragon Jake Long, and not simply because of the connections to Chinese culture. Rather, MK is a very similar character to Jake, from his impetuous nature to his constant use of “hip and popular” vernacular. That said, while Jake’s use of slang could get obnoxious (something the show runners on Jake Long noticed and dialed back in its second season), I find this isn’t really the case with MK.

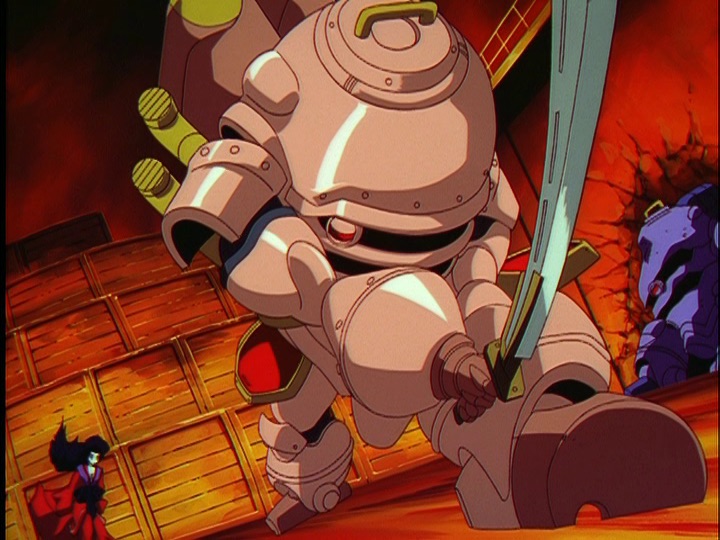

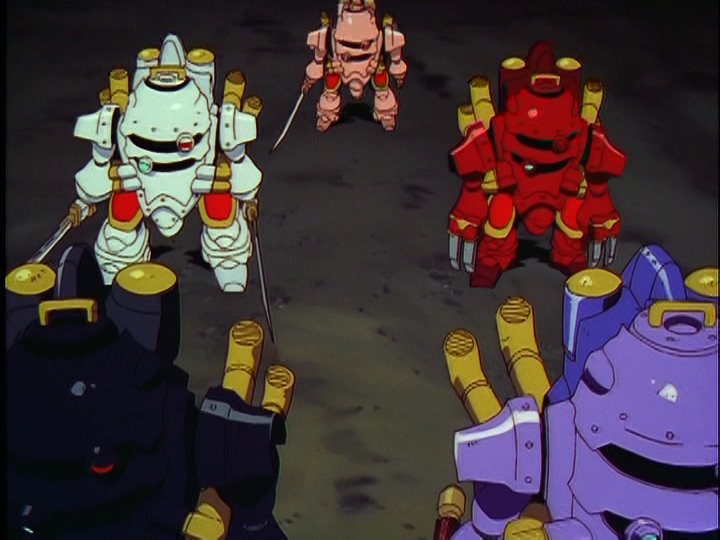

Another cartoon that came to mind was Thundercats, and with it all the 1980s action cartoons of that variety. Specifically, in the storyline, the Demon Bull King is weakened after his revival, and is forced to rely on cybernetics that are powered by artifacts. Items of sufficient rarity (from ancient treasures to exclusive sneaker drops) can restore him to his former might, but only temporarily. This kind of Mumm-Ra/Silverhawks MonStar villain hasn’t really been a thing for a very long time, which makes Monkie Kid’s decision to include such a gimmick oddly nostalgic for someone my age.

The approach to storytelling is mostly episodic (as opposed to outright serial) and full of toy-shilling antics, but it does build towards major events here and there while featuring actual character growth along the way. Again, I liken it to 80s fare wherein a few episodes and a season finale are more focused on the overarching plot, and the results are usually pretty satisfying if one doesn’t mind this format. One big edge Monkie Kid has, however, is that it doesn’t feel as aimless as Thundercats or He-Man, and even displays shades of Avatar: The Last Airbender in the way it gradually turns into a grander and more epic story.

It’s also obvious that the show creators are more than aware of Avatar when Monkie Kid throws in gag references to Aang’s spinny hand trick. In fact, this is just one of many shout-outs to past animated works.

There’s one fun detail about Monkie Kid that I think is worth mentioning: The casting choice for the Monkey King. In English, he’s actually voiced by Sean Schemmel, the current dub voice of Goku from Dragon Ball Z—in other words, a guy famous for playing a Sun Wukong derivative is voicing the original! And then in the Cantonese and Taiwanese Mandarin versions, the role is performed by Dicky Cheung, a Hong Kong actor who rose to fame portraying the Monkey King in the popular and beloved 1996 Journey to the West TV series!

(He also sang the openings for those versions too.)

Overall, Monkie Kid is a children’s cartoon with real legs. Though it may be based on Legos, and it’s not the most sophisticated thing, there is an undeniably high quality to the whole thing. It’s one of those works where the creators definitely did not need to go this hard, but they chose to elevate their project into something greater. I come out of this now curious to watch whatever comes next, and maybe try to finally read Journey to the West.