On a recent trip to Japan, I walked past a shrine. Next to that shrine were statues of Dragon Quest monsters. Seeing them reminded me of the sheer impact of those games and the artist whose memorable designs helped to entrench the series in Japan’s popular imagination.

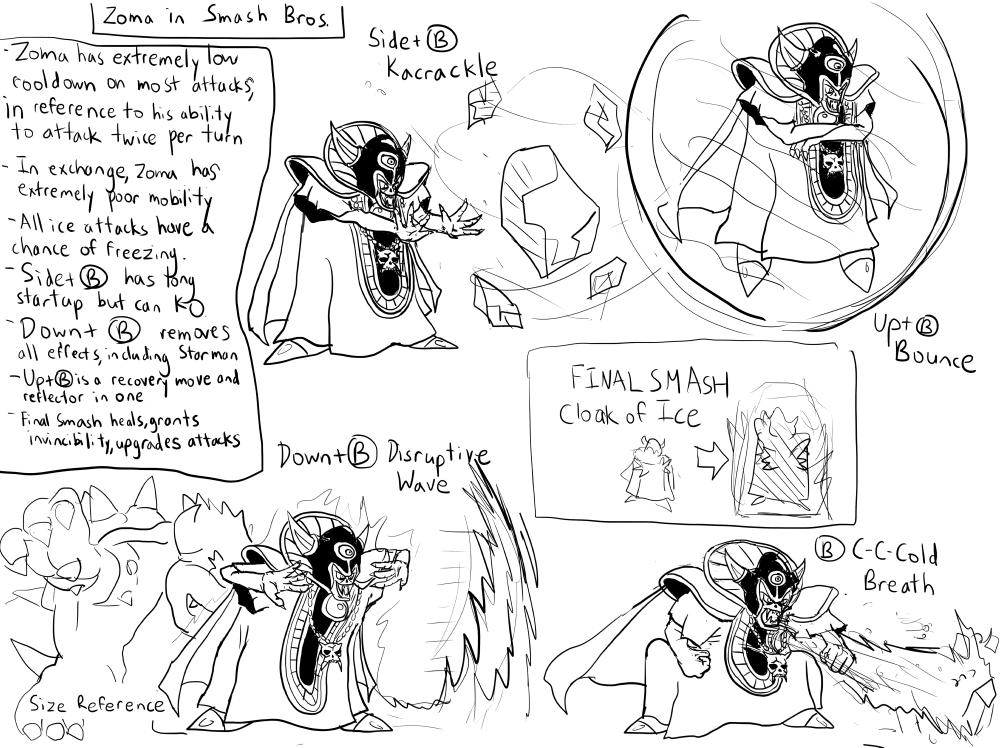

We now live in an age where Toriyama Akira is no longer with us. As the creator of Dragon Ball and Dr. Slump, as well as the iconic artist of Dragon Quest and Chrono Trigger, his influence is nigh-unmatched. There are maybe two or three other series that are as pivotal to shounen manga as Dragon Ball, and Toriyama even casts an enormous shadow on the isekai and fantasy genres: The Dragon Quest series is what established the “Hero” (Yuusha), the “Demon Lord” (Maou), and the “weak Slime” as archetypes in Japan’s popular imagination, and it’s Toriyama’s designs that inform the aesthetic of all successors.

In light of Toriyama’s tragic death at only 68 years old, I’d like to just talk about how my life has been touched by his work. My story is nothing special compared to the millions of voices mourning Toriyama, but I wanted to at least personally add to the well wishes pouring out.

Dragon Ball

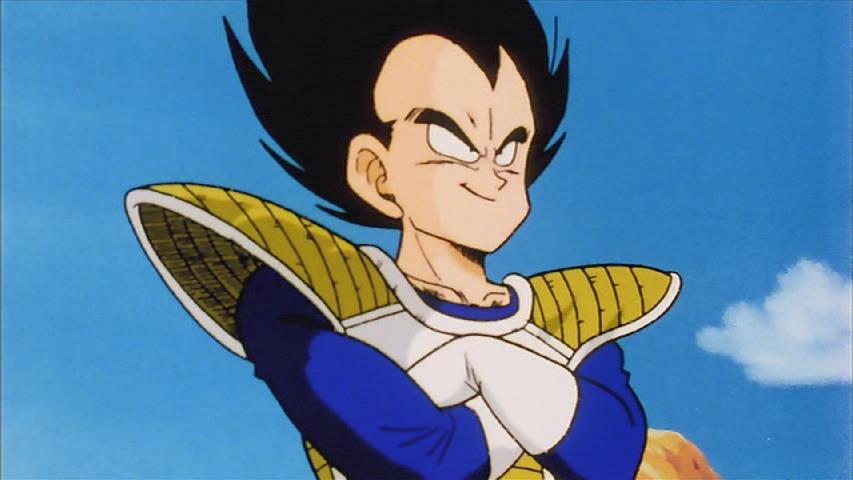

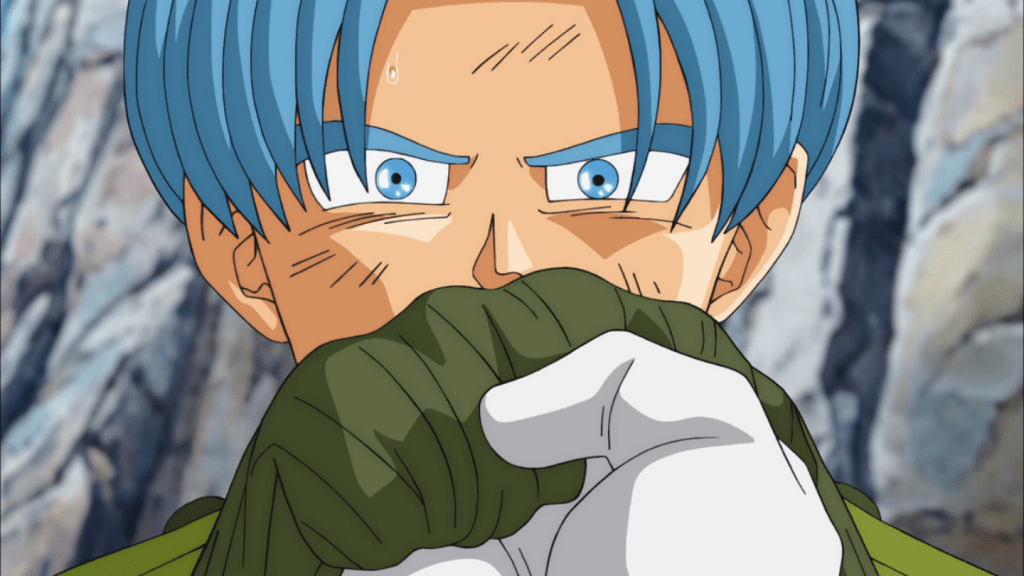

Dragon Ball Z was the very first anime that I knew to be “anime.” While I had loved things like Voltron, they were still just “cartoons” to me. But when a relative started bringing home tapes of DBZ, it was a sight unlike any other. I remember just being amazed at the rapidfire punches, the zooming around, the ki blasts—I’d never realized animation could be this way! I cheered for Piccolo, watched characters (gasp) die, saw Son Goku turn Super Saiyan, and witnessed his son step up and defeat Cell. I wondered if anything could ever top this story. I wanted to be Gohan.

It was also a time when I got to play the first two fighting games for the Super Famicom, and when I’d re-read over and over a small guide to the first game that showcased all the playable characters. “What does Jinzoningen (“Android”) mean?” I recall wondering.

So when I first found out that DBZ was coming to US airwaves (for real, and not just finding a random channel that sometimes had Korean episodes of the original Dragon Ball), I was elated at the prospect of Dragon Ball Z getting big. Imagine: more American DBZ fans! While the English adaptations have had their differences with the original (as well as the non-English dub I first watched), Goku ultimately succeeded in reaching into the hearts of countless viewers. (I still wish those early US viewers got the chance to hear “Chala Head Chala,” though.)

Ironically, I was one of those people who’d go on to poo-poo the Dragon Ball franchise. As I got more into anime and manga, I viewed the series as a thing you’re into when you’re just a “beginner,” or obsessed with just macho violence and watching muscle-bound dudes power up endlessly, and I felt good that I knew there was more out there. It took a number of years to get through that embarrassing phase, but I’d eventually come back around to appreciate Dragon Ball for its outsize influence on culture, as well as for just being a work of art in itself. More recently, it’s been great seeing Dragon Ball Super be a thing, and for Toriyama to have worked to bring back the essence of Goku—as well as the balance of action and humor that Dragon Ball and Toriyama himself had been known for.

Dragon Quest

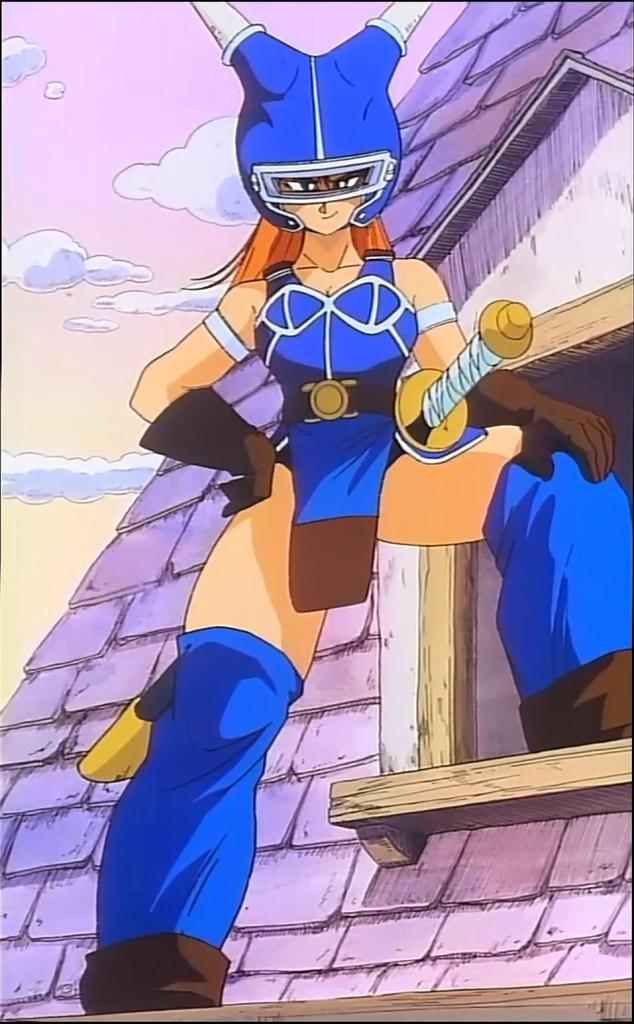

Dragon Ball Z was actually not my first encounter with Toriyama, and not even the first anime from Toriyama that I had seen. I was one of the kids who watched Dragon Warrior (aka the English dub of the anime Dragon Quest: Legend of the Hero Abel) as it aired. I remember having to wake up very early—around 5:30 or 6am on weekends. I don’t think about it very often, but in hindsight, the show was likely very formative for me, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Daisy (the girl in blue armor) ended up influencing my taste in characters.

My family also subscribed to Nintendo Power, and we received a free copy of Dragon Warrior (aka the first Dragon Quest) as a result. Today, RPGs are a popular and beloved genre of video game, but back then, they were entirely new territory to most kids, and pretty unapproachable. However, the same relative who brought home DBZ tapes had decided that they were going to beat Dragon Warrior, and spent hours getting through the game as a young me would watch along. In the final battle, the evil Dragonlord reveals his true form as a giant bipedal dragon, and I remember just being in awe.

This was at a time when the Super NES had already come out, and I thought the Dragonlord looked almost on par with the graphics I saw there. The fact that his foot covered part of the dialogue box, and the way the screen froze instead of shaking every time he landed a blow made it feel like this was the ultimate adversary. It wasn’t until at least a decade later that I got to see Toriyama’s drawing of the Dragonlord that I realized just how closely the sprite graphic matched his original art, and I appreciated that memory all the more.

If Dragon Warrior was the game that pushed the boundaries of what an NES game could look like, then Chrono Trigger was a revelation. The 16-bit graphics and the greater color palette of the Super NES really brought Toriyama’s designs to life, and the game conveyed an intensity to RPG battles unlike any I’d seen up to that point. The only thing they paled in comparison to was Toriyama’s actual drawings of Chrono, Frog, Magus, and the others. While Chrono very obviously looked like a redheaded Goku, he was still unbelievably cool. And just as the Dragonlord was a mindblowing antagonist, so too was Lavos. The eeriness of music and visuals in the climactic confrontation with him is hard to match even to this day.

Years down the line, Dragon Warrior finally became known as Dragon Quest just like in Japan, and I was one of the folks who bought Dragon Quest VIII. It wound up being one of my favorite RPGs ever. In addition to its classic feel (Dragon Quest is famous for not trying to reinvent the wheel), the game really felt like stepping into the world of Toriyama’s art. It was a triumph of the PlayStation 2, but also a treat for those who always wanted to see an interactive environment that embodied his imagination and aesthetic.

A Farewell

Toriyama Akira’s life was a spark that inspired creators to bring their ideas to life, bridged culture gaps through the sheer power of his work, and even pushed people to exercise and train so that they could be like Goku. His name is synonymous with anime, manga, video games, and even indirectly light novels. And while I can’t call myself the most diehard Toriyama fan, he clearly took my life on a course that would embrace the wonders of Japanese popular culture—a path I still pursue to this day. Rest well, King. To say you deserve all your praise and accolades is the understatement of a lifetime.