Whether by circumstance or choice, I’ve had the benefit of knowing, learning, and at the very least being exposed to multiple languages. I’m native in one, grew up with a second, and work extensively with a third (Japanese). I love learning about languages. However, as I try to improve my understanding, I keep running into a couple of issues where I feel that I probably know the answers but am afraid to fully open my eyes.

First, what language(s) should I be focusing on? One connects me to my background and culture. Another helps me professionally. And then there are a few others I’ve been exposed to over the years that I’d like to at least get a grasp on.

Second, if I want to get to a point of fluency in a language, what do I need to do? For that matter, what kind of fluency am I looking for?

From my having studied Japanese, I’m aware that there is a point at which a language will just click into place. I have vivid memories of having spent time there after taking classes back home, and one day just being able to understand so much more, as if my brain finally “got it.” So the best solution to start with is probably to stick with one language until it entrenches itself in my mind, because outside of head trauma, you can’t ever fully lose it.

I also know this because my second language is something where I have an intrinsic connection. My parents have spoken it all my life, though I haven’t always reciprocated in kind. I’ve spent much of my life in a situation where I can often understand what is being said to me but can’t always find the words on command, and my reading ability is subpar at best. When it comes to really complex topics or idioms, I am out of my depth. Even so, I can tell that it’s in settled deep in there. My specific dilemma here is whether I should be satisfied with only that much.

So the specific goal depends on the language because I have different degrees of familiarity with each. When it comes to Japanese, I would seek a greater mastery so that I won’t get caught off guard by unusual words or phrases, be they extremely archaic or all too modern. For my parents’ tongue, I’d like both literacy and enough of an expanded vocabulary so as to not sound like a child even well into my adulthood. And as for other options, I’d really just like to be able to read comics in a target language so I can appreciate them more.

The hard pill for me to swallow is that the best thing to do, almost without a doubt, is to concentrate heavily on one so that the neural connections can form. Be as active as possible about it too, consuming all the media I can, and maybe even seek out language partners or take classes. From there, once I feel comfortable with one, I can maybe consider trying another.

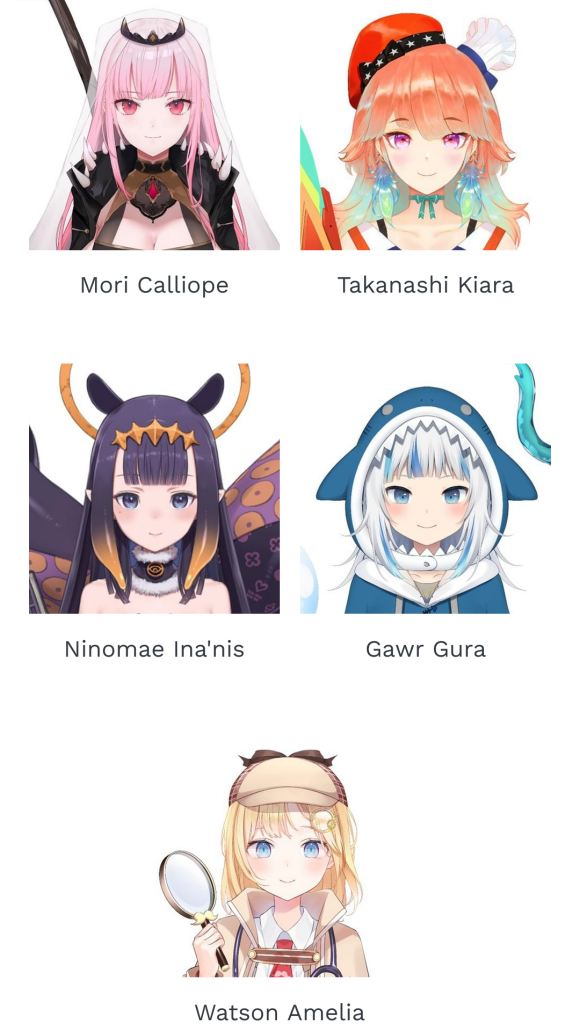

However, there are some barriers, mostly having to do with time and mentality. While I’m very fond of language learning, it’s not my only hobby or even my primary one (see: this anime and manga blog). Also, whenever I stray away from a language, I end up feeling guilty about neglecting it—even if it’s to work on another one! Despite knowing full well that learning new languages is hard, I feel stuck in limbo, worried that I’m simultaneously spending too much and too little time and effort. If I can overcome that block, I can probably make greater strides instead of moving forward bit by bit.

My intent is not to become a polyglot. I don’t have a goal of wowing my friends with all the languages I can possibly speak. If I were to achieve such skill, I’d surely be happy about it, but it’d be just one more tool I could utilize to explore the world and its stories better than ever. Now, if only I could make sense of my jumbled thoughts.