Shoujo Fight by Nihonbashi Yoko (released in English as Shojo Fight) is my favorite volleyball manga. Yes, even more than Haikyu!!, and even more than Attack No. 1. The series is great in so many different ways, but I think the key is how it manages to succeed at being both a story about volleyball and a story with volleyball in it. The drama is compelling on- and off-court, and the characters’ continued growth in both arenas feels both organic and satisfying.

This isn’t the first time I’ve written about this manga, but after 16 volumes released in English digitally by Kodansha, I realized I’ve ever written a proper review to talk about why I love Shoujo Fight so damn much. Now I’m here to correct that oversight.

Shoujo Fight is the story of Oishi Neri, who we first meet as a second-stringer on the prestigious Hakuunzan Middle School Girls’ Volleyball Team. Although she may seem unfit for the sport, it’s soon revealed that she’s on the bench not for a lack of talent, but because she voluntarily chooses to hold herself back for fear of alienating her teammates. Volleyball has been her way to cope with major trauma in her life, but the intensity with which she plays drives others away. After Neri is mistakenly kicked off the team due to a supposed sex scandal, she is unable to join Hakuunzan’s high school division and instead ends up at Kokuyoudani High: a school infamous for its heelish misfits. However, it’s only by joining their volleyball team that Neri begins to find teammates who will accept her flaws, help her overcome them, and even recognize when they’re actually strengths.

Neri alone would be enough to carry the series and keep me hooked, but I can’t emphasize enough that the entire cast of characters is incredibly strong and memorable, from major to minor figures. Not only do they have outstanding personalities that rarely come across as one-note, but they develop in interesting ways too. As players, their strengths and weaknesses on the court give hints as to how they approach the game and how they function within teams, but Shoujo Fight also explores how these qualities within the context of volleyball are but fragments of whole human beings with thoughts, feelings, fears, and dreams.

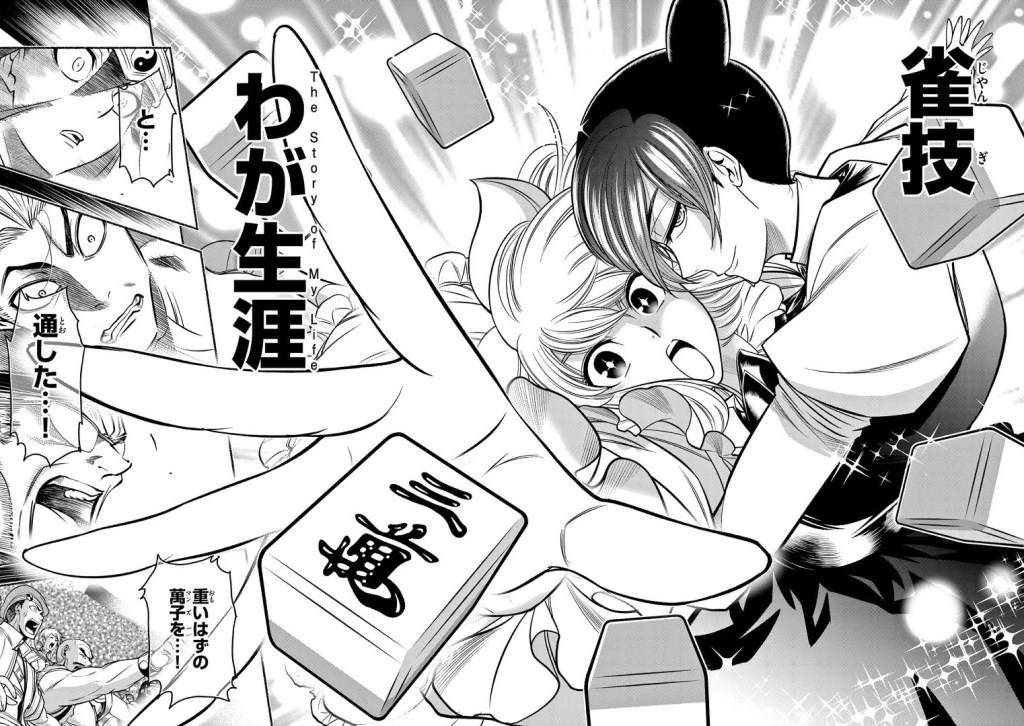

Aside from Neri, the best example of character growth in Shoujo Fight is Odagiri Manabu, a nerdy girl who starts off as an old classmate of Neri’s more interested in drawing manga in class, and who looks up to Neri for her inner strength. She eventually joins Kokuyoudani’s team just to try it out, and though an absolute novice in every way possible, the senior members of the team see something in Manabu. Her personal traits of kindness, thoughtfulness, and sense of imagination gradually translate into volleyball and take her on the path to becoming a great setter.

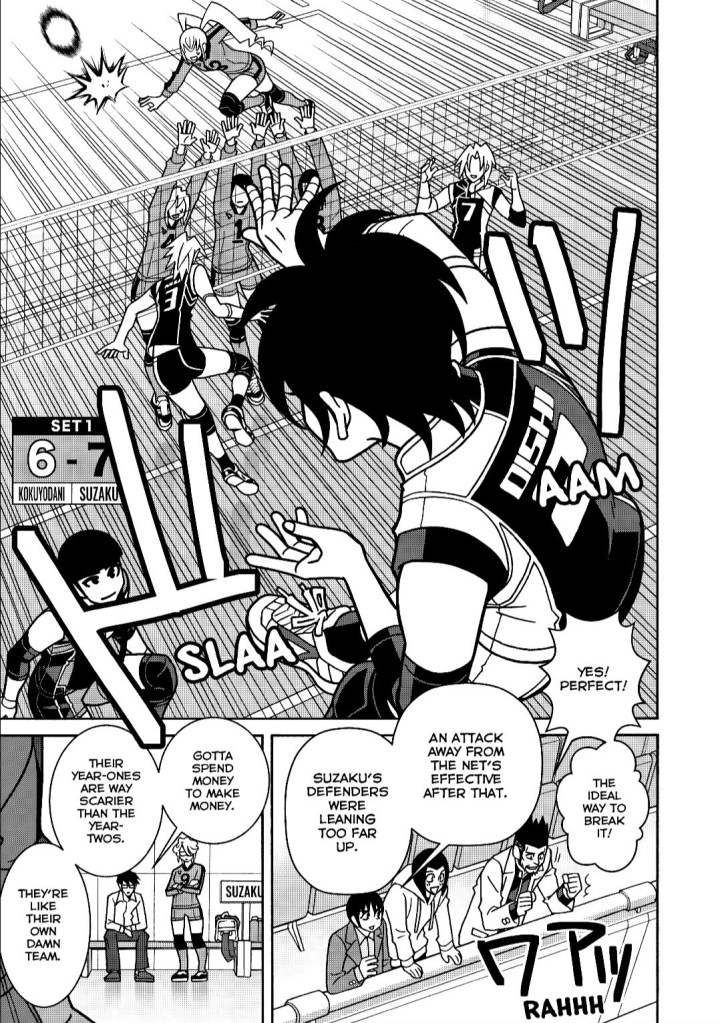

My favorite character by far, though, is captain Inugami Kyouko. As Kokuyodani’s premier setter and master strategist, her coming onto the court spells trouble for the other team every time. However, her lack of stamina (due to being asthmatic) means she can only provide a temporary boost. Not only does this make for exciting moments, but she is shown to purposely based her play styler around being a shot in the arm. More importantly, though, she is a practical jokester par excellence whose masterful trolling is also a result of skills honed due to the limitations of her physical condition. Her mischievous personality combined with her keen game sense means that she can swing from serious to silly and back, and it never feels out of place. Though, that’s not actually something exclusive to Kyouko—Shoujo Fight as a whole does a great job of expressing both the dramatic and comedic at once.

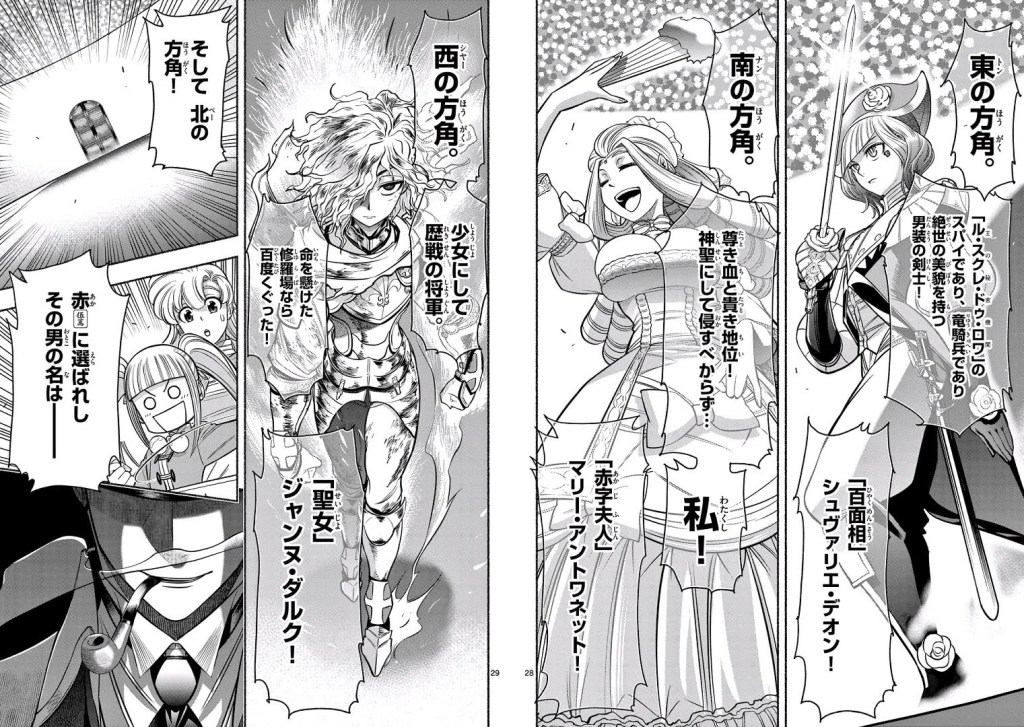

When I say that it manages to somehow both be about volleyball and simply include it, what I mean is that the sport can act both as background and foreground depending on which storyline is involved. When it’s about team rivalries or maybe animosity between two players, then the game of volleyball and all its quirks are front and center. When familial political maneuvering is happening and characters are caught up in it, then volleyball becomes the backdrop through which the drama plays out. They’re two sides of the same coin, and often it’s hard to tell what’s heads and what’s tails. For example, while Shoujo Fight doesn’t really have “antagonists” per se, one character introduced later is basically a woman with deep pockets and a lot of clout whose desire to build stronger national volleyball teams sees her going as far as to manipulate families into arranged marriages for both political convenience and to create super athletes. Shoujo Fight never feels like merely an ad for volleyball or the power of friendship in volleyball, but it’s also not above celebrating these concepts.

Shoujo Fight is, in essence, a manga where a variety of dueling contradictions come together to make something greater than the sum of its parts. Its energy is pure and innocent, yet also down and dirty. Its storylines and characters can be filled with ennui yet lighthearted as it gets. High school feels like Neri and the others’ entire world but also just a temporary stop in life. Shoujo Fight is all things, and it’s a world that’s both amazingly accessible and remarkably deep.