The day that Ryu from Street Fighter was announced for Super Smash Bros. for 3DS & Wii U was a milestone: the first time a traditional fighting game character would appear in Nintendo’s iconic crossover series. But if Ryu is undoubtedly the most appropriate representative of the 2D fighter, then Akira Yuki from Virtua Fighter would be my pick for 3D fighter’s poster boy. After all, Virtua Fighter was the series that introduced 3D fighting games to the world.

Akira represents a unique challenge in terms of translating his character to the world of Smash. While he has many surface similarities with Ryu—both are short-haired, Japanese, bandana-wearing martial artists focused heavily on their craft—they have almost the exact opposite functions in their respective games. Whereas Ryu is generally considered an ideal beginner’s character who’s easy to learn but whose mastery teaches the fundamental aspects of Street Fighter, Akira is meant for experts alone. The Virtua Fighter character is notoriously unforgiving to use, as it is absolutely necessary to master his extremely tight execution requirements to do any combos or damage. In fact, novices don’t even have the benefit of button mashing and hoping for the best, because his design actively prevents button mashing from being effective.

Capturing this “advanced players only” quality in Akira, as well as the general gameplay and feel of his fighting style in Virtua Fighter, is what I would prioritize when making him into a Smash character. Virtua Fighter itself is considered a game with fairly simple controls (3 buttons, 1 joystick) but whose competitive depth makes it feel like you’re outwitting your opponent first and foremost, even when characters like Akira have such high execution requirements. That’s also why this entry is so much longer than previous Smash character concepts—it’s necessary to show how Akira would embody Virtua Fighter.

Fighting as Akira should feel like you’ve out-thought your opponents, and your reward is a highly refined punish game consisting of short and sweet combos that nevertheless do scary amounts of damage. Fighting against him should make you feel bad for getting called out over and over for your predictability. At the same time, execution shouldn’t be too difficult, as it goes against the spirit of Smash Bros., but should be tricky enough that you can’t just buffer and mash and succeed. In terms of general stats, Akira would be heavier and slower than Ryu, and would of course lack a projectile move. He would be below mediocre in the air, given that Virtua Fighter characters are typically not known for their leaping prowess, and would be vulnerable to edgeguarding. On the ground, however, Akira would be a menace in a way Little Mac isn’t. He would have fast attacks with poor recovery time, rewarding intelligent exploitation of rock-paper-scissor scenarios but punishing Akira for bad decision-making and guesses.

Specials and Other Attacks

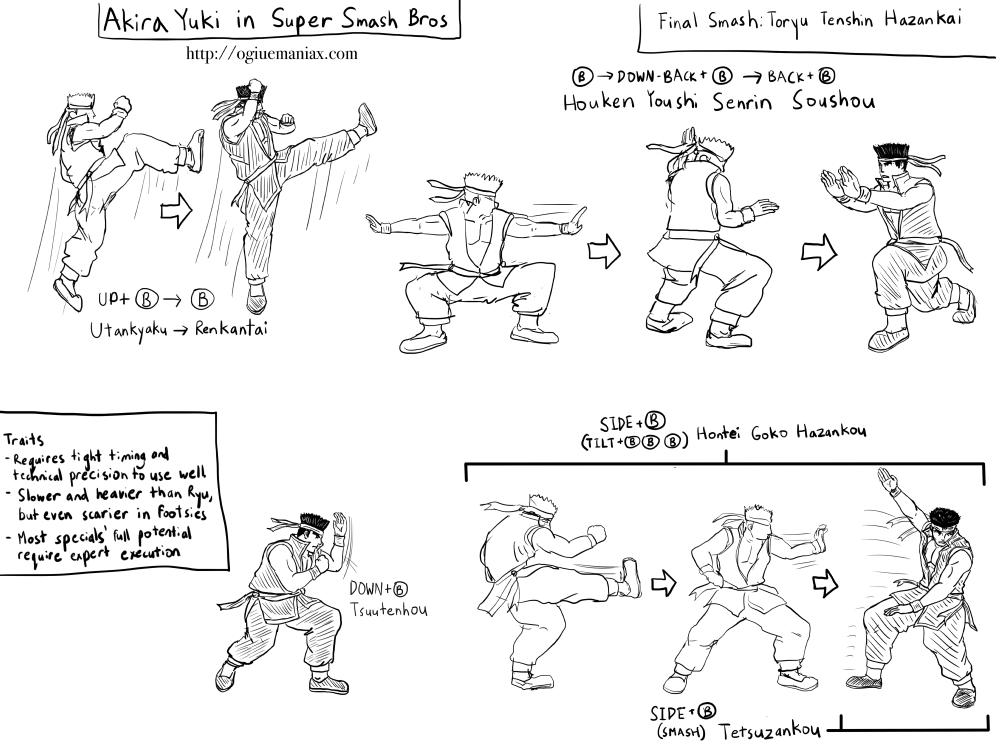

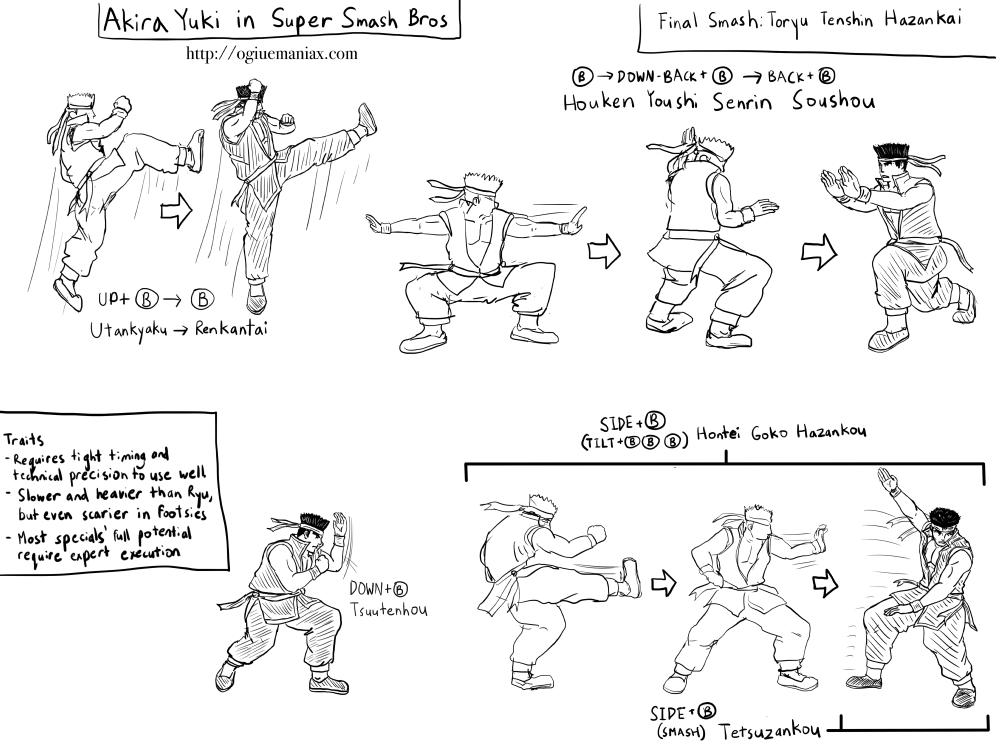

The special moves depicted above are meant to show that Akira has multiple options open as one attack flows into the next, but there’s usually a choice that’s 1) more powerful, 2) more difficult to execute, and/or 3) comes at a higher price. Take Akira’s side special, for example. If you tilt the stick, you get Hontei Goko Hazankou, a multi-part attack similar to Marth’s Dancing Blade. It does decent damage, and the initial kick can actually negate the intangibility on rolls and directional air dodges (but not side steps or neutral air dodges). The third part of the attack is Akira’s signature Tetsuzankou body check (and Bayonetta’s forward throw!), which does decent damage and can KO at very high percents. However, if you do a smash side-B, it becomes a raw Tetsuzankou, and like in Virtua Fighter, it is much, much more powerful.

In particular, there is an initial Tetsuzankou hitbox very close to Akira’s body that does massive damage (something like 30%) and can KO at early to middle percents. Even the late hitbox as Akira moves forward can do around 20%, but it’s highly punishable on dodge or shield. Another variant is that if you smash side-B back (as in the opposite direction that Akira is facing), he performs a back-turned Tetsuzankou, which is just as strong as the forward-facing one, only a few frames faster. In other words, roll past him at your own peril.

Perhaps Akira’s most famous technique is the “Houken Youshi Senrin Soushou” combination, known to English-speaking fans as the “Stun Palm of Doom.” In the Virtua Fighter games, this move is notorious for being difficult to execute, requiring precision and timing that could make even some Melee fans recoil. To reflect this challenging element of the move, hitting neutral-B alone would not do the full move. Instead, you need to hit neutral-B, down-forward-B, then back-B in that exact order at a very specific timing for each part. And unlike with Akira’s Tetsuzankou, you want to perform this whole thing successfully every single time, though stopping at Youshi Senrin (the second part) can open up certain options that can potentially lead to more damage. Also, the move is extremely unsafe on block, so you can’t just spam it and hope the opponent will get hit. You need to be confident that the Houken is going to land, because you pretty much need to execute the rest before the first part has even landed.

Ironically, his Final Smash, Toryu Tenshin Hazankai actually does less damage overall compared to Houken Youshi Senrin Soushou.

As for Akira’s other moves, Utankyaku is pretty bad as a straight-up recovery move (but it has its merits on offense) and Tsuutenhou is a unique “counter” move of sorts. Hitting up-b once makes Akira do a leaping kick called Utankyaku. Hitting the b button again results in a second kick, turning the move into Akira’s Renkantai. Both parts are capable of KOing, and the question as to whether it’s going to be one kick or two can mix up opponents. As for the down-B Tsuutenhou, it’s an upward strike that can knock opponents off balance if it’s used to interrupt an attack, and can lead to devastating follow-ups, but it’s sort of a backwards counter as it’s more effective against quick attacks than slow ones. If Akira can’t do a powerful punish in time, he can hit down-B again and default to Moukou Kouhazan, a simple palm strike. Akira also has a crouching dash like in the Virtua Fighter games, though in this case it’s performed by just smashing down-forward or down-back.

Akira actually has one other “hidden” special move that’s an Easter egg of sorts for Virtua Fighter fans. By hitting B and shield and letting go of shield after exactly 1 frame, Akira can perform Teishitsu Dantai, a quick knee strike that pops the opponent up and makes them vulnerable to combos. And for the sake of keeping this already long description from being more unbearably wordy, I’ll briefly say that most of his most iconic moves will be found in his normals. His smash attacks, for example, would be Byakko Soushouda, Chouzan Housui (negates side steps and neutral air dodges and does heavy shield damage if charged), and Youshi Saiken. Certain attacks (such as Tetsuzankou) would be able to power through projectiles uninterrupted, making playing keep-away fairly effective against Akira but not a guaranteed success by any means.

Overall

The resulting character is one that would really rewards players who love challenging execution and challenging mind games alike. If there are heart, body, and brain players each representing different tendencies in approaching fighting games, Akira Yuki would reward the body player who can also master the intuition of the heart and the disciplined research of the brain.