WARNING: SPOILERS FOR THE FIRST GAOGAIGAR VS. BETTERMAN NOVEL

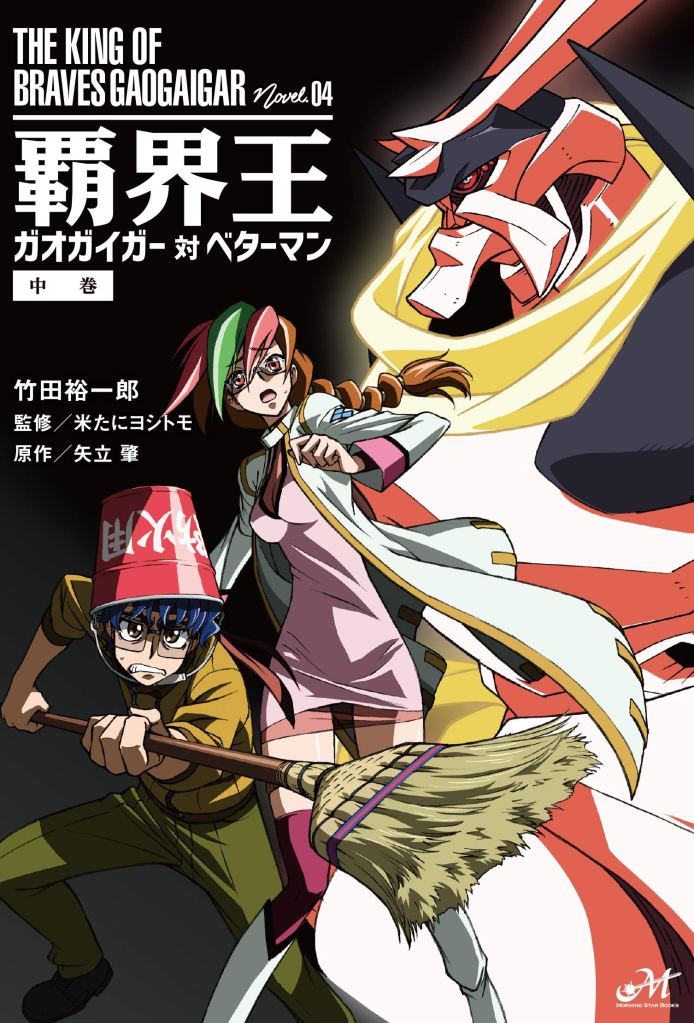

The Hakai-oh – Gaogaigar vs. Betterman web novel series has been a blessing for giant robot fans. Taking place in the Gaogaigar universe ten years after the cliffhanger ending of the Gaogaigar FINAL OVAs, it tells the story of how the world has changed since the Gutsy Galaxy Guard got trapped in another universe, and the new challenges those on Earth must face. A now twenty-year-old Amami Mamoru has gone from plucky kid companion to a seasoned robot pilot in his own right, working alongside his fellow alien adoptee Kaidou Ikumi to control Gaogaigo, a successor to the King of Braves in the fight against the forces that threaten the world. The series is being collected into print novels, and that’s the way in which I’ve been reading it.

The end of Part 1 saw the triumphant return of Shishioh Guy, the original pilot of Gaogaigar. However, his comeback was not without cos,t as the robot lion Galeon nobly sacrificed itself to free Guy from the clutches of their mysterious god-like adversary, Hakai-oh (“World-Conquering King.”) The second novel, Part 2, picks up directly from that point with a new challenge: a reunion with some old and familiar faces, not as allies but as enemies. Guy and Mamoru must fight across the world, respectively as the Mobile Corps Commanders of the Gutsy Galaxy Guard (GGG Green) and the Gutsy Global Guard (GGG Blue).

Genuine Care for Lore and Characterization Alike

When I read Gaogaigar vs. Betterman, I’m always struck by how much attention is paid to its own history and lore. While it can sometimes get a little too into the weeds, the general feeling that comes across is real affection and respect on the part of the creators for the universe they’ve created, as well as the fans who have embraced these stories. From the way fights play out to moments of character introspection, everything and everyone is portrayed with a robust three-dimensionality that rewards readers who remember both Gaogaigar and Betterman.

For example, we’re reminded that Neuronoids (the robots of Betterman) are powered by artificial brains based on neurological patterns of actual species. This novel answers the question of what brain is in Gaogaigo: a dolphin from the Gaogaigar video game who was turned into a G-Stone cyborg like Guy, and who ultimately had to pass when the “Invisible Burst” that compromised electronics before the successful establishment of the Global Wall made it impossible to maintain the dolphin’s cybernetics. During a fight, it’s revealed that Gai-go is actually extremely strong in underwater combat—a product of being based on a marine creature.

There’s also a side story at the end of the novel that takes in the space between Part 1 and Part 2, where Guy and Mamoru visit a transit museum to see the original Liner Gao, the bullet train that becomes the shoulders of the original Gaogaigar. As they converse, the topic of the Replicant Mamoru from Gaogaigar FINAL comes up. While Repli-Mamoru ended up being merely a clone of the real Mamoru, Guy still carries a lot of guilt over killing him—especially because Guy hasn’t aged and still remembers that trauma as if it were mere weeks ago. It would have been all too easy to forget that part of the OVAs, especially because of the grandiosity of its later battles, but both the author (former Gaogaigar staff Takeda Yuuicihirou) and supervisor (the original director, Yonetani Yoshitomo) put in that extra mile.

As a funny little moment during this side story, Guy is less astounded by the giant “Global Wall” defense system that allows wireless communications to work after a previous disaster than he is by Mamoru’s smartphone. When he last left, beepers (like Mamoru’s special GGG version) were still the norm, and to see the progression of human technology (as opposed to G-Stone technology derived from Galeon) puts a smile on Guy’s face.

Spotlight on Betterman

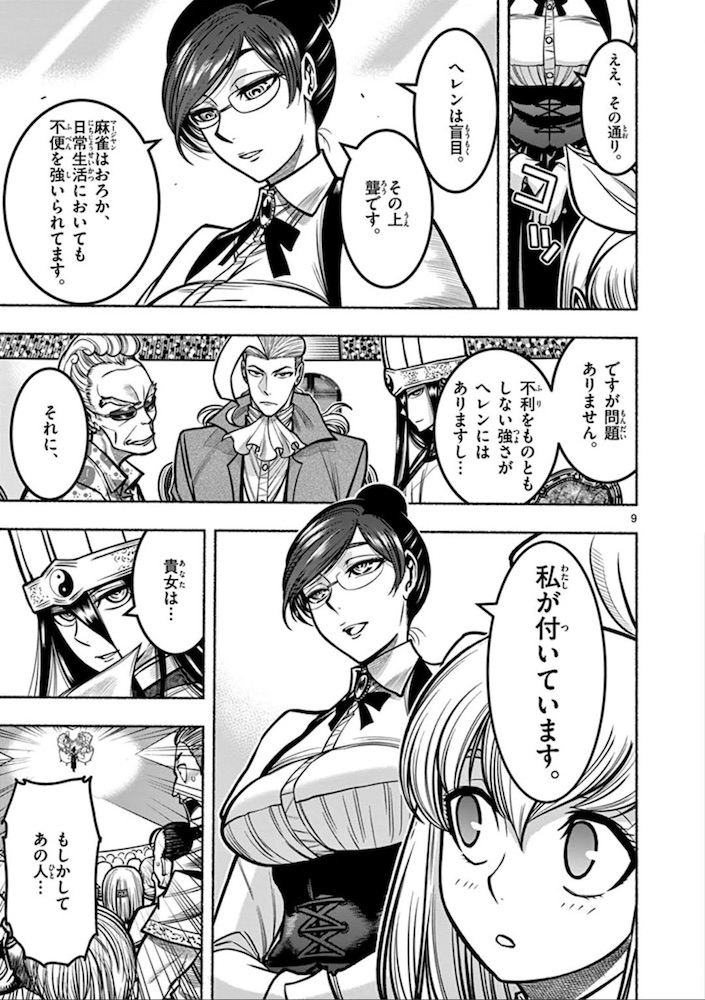

Because Gaogaigar is the bigger franchise between the two marquee titles, it gets the (robot) lion’s share of the attention overall. However, Part 2 does devote more pages to the Betterman side of things than previously—while the first novel’s Betterman-focused pages are mainly about the Somniums (the titular “Bettermen”) and the question of whether they would help defend the Earth, this novel explores the original main characters, Aono Keita and Sai Hinoki, in greater detail. In particular, Keita was a relatively minimal factor in Part 1, but here, his romantic relationship with Hinoki is front and center for a significant portion of the book. Keita’s portrayal is interesting because of how humble his situation is. Rather than staying in space with Hinoki (who has since become highly educated and is a science officer for GGG Blue), Keita is without a college degree and works at an electronics store, where his otaku knowledge makes him an ideal employee. But Keita also works hard with the dream of providing a home that Hinoki can come back to, especially because Hinoki tragically lost her family as a young child.

The color insert at the beginning of the novel also has colored design images of Keita and Hinoki courtesy of the original character designer, Kimura Takahiro. As a huge fan of Kimura’s art (and his work creating Hinoki), it’s a welcome addition.

Intense(ly Clever) Battles and the Value of Experience

The real meat and potatoes of Part 2 are the many fights that take place throughout. Because they’re a pretty major surprise and make up such a huge portion of the story, I’m going to put an extra SPOILER WARNING here.

While there’s a bit of fighting between Guy and Betterman Lamia that makes the Gaogaigar vs. Betterman title technically true, the main thrust of conflict in Part 2 comes in the form of the old Gutsy Galaxy Guard members who have now been taken over by the “Triple Zero” energy that comes from Hakai-oh. Now greatly powered up and known as the “Hakai Servants,” Brave Robots and human GGG agents alike now fight against the Earth with the goal of bringing “divine providence” to the universe.

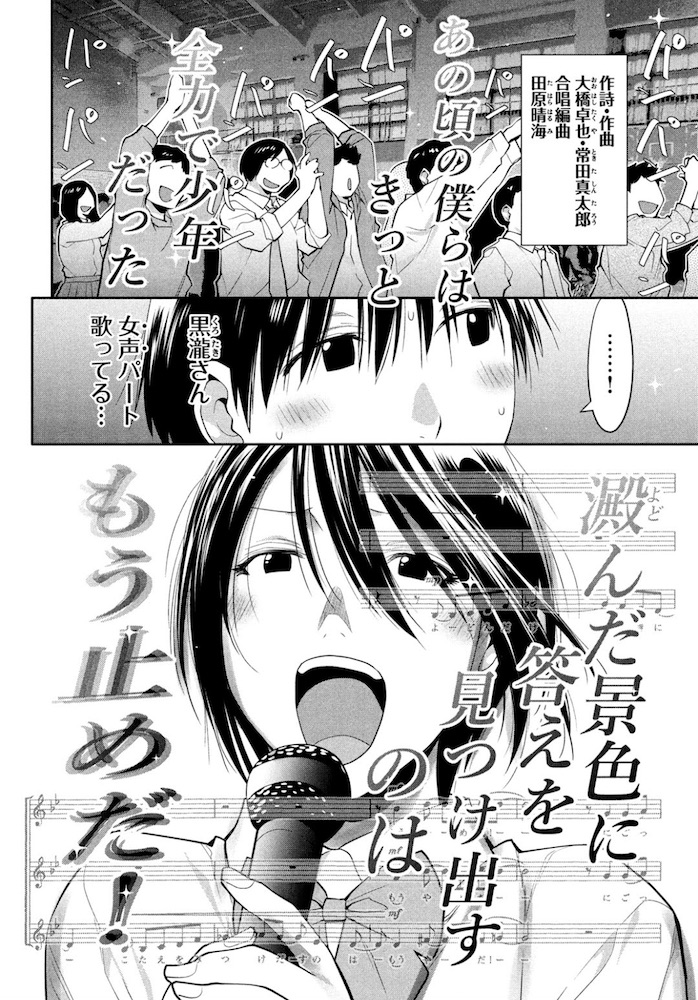

The first character who shows up to oppose the heroes is actually Hakai Mic Sounders, and I will say that “Evil Mic Sounders” is indeed quite a trip. Still using his characteristic mix of English and Japanese, it’s easy to not take a line like “SORRY, but I have to destroy you” seriously—that is, until you’re reminded of how powerful Mic truly is. With the ability to produce sound waves that can break down anything (if given the right information), Mic Sounders is capable of rendering even the toughest armors useless. The only reason they win is because a Betterman who can control sound herself is able to provide a counterbalance.

That battle introduces the recurring idea in the fights against the infected Brave Robots: GGG is a great asset when on the side of humanity, but beyond dangerous when its powers are turned against Earth. Goldymarg’s signature toughness (enough to withstand the power of the Goldion Hammer when in Marg Hand form) makes him able to withstand just about anything, and it takes a “Goldion Double Hammer” weapon wielded by Guy in Gaofighgar to even begin to even the odds. Tenryujin and Big Volfogg make for similarly intimidating opponents with their own unique strengths, Volfogg’s role as guardian of a young Mamoru in the past providing an extra layer of stakes in that particular fight. But it’s also not just the robots who are a threat—the human members have also become Hakai Servants, and the tactical prowess of Commander Taiga and the genius hacking skills of Entouji provide extra hurdles for GGG Green and GGG Blue.

Another recurring theme throughout these fights, however, is that the time dilation difference between the old GGG members and the current ones means that Mamoru and the others have ten years of their own experience under their belts. There’s a moment at the beginning of the novel where Mamoru says that he’s willing to relinquish the role of GGG Mobile Corps Commander to Guy, only for Guy to reject his offer and to praise Mamoru for having clearly been through many tough trials of his own, and at this point actually has fought with GGG for longer than he has. He further explains that he was originally just the right man for the moment, having been an astronaut transformed into a G-Stone cyborg to save his life, and wasn’t a born fighter himself.

And so we see that sentiment play out. In the fight against Tenryujin, her younger “sister” Seiryujin, the latter targets Tenryujin’s knees—a seemingly odd move, until one remembers that the individual robots that compromise the “Ryu” series all turn upside down to combine, meaning their chests (and thus their Hakai-infected AI boxes) are located in the legs. When dealing with Entouji’s computer virus, GGG Blue member Inubouzaki Minoru takes center stage. Originally a jealous rival of Entouji’s who became a Zonder in the TV series, and later returned as an ally when the Gutsy Geoid Guard became the Gutsy Galaxy Guard, Inubouzaki shows the progress he’s made the past decade not only in terms of improved skills but also being more at peace with himself and his past.

Just as everything seems to be going Earth’s way, however, the next Hakai Nobility appear: Goryujin and Genryujin (who both have access to THE POWER), as well as Soldat J and King J-Der. The preview of the next (and last!) volume hints at what’s to come with the key to victory: something called “Goldion Armor.”

To the End

The web novel version of Hakai-oh – Gaogaigar vs. Betterman has concluded, and the concluding print release is supposed to be out this summer. While I could jump in and start reading it online now, I think I’m going to wait once more. If I could wait close to 15 years before, I can withstand a few months.

In the meantime, I’ve also been reading the manga adaptation of this series, which provides some of the visual flair that’s inevitably missing from the prose version. I can only hope that we might see an actual anime come out of this someday.