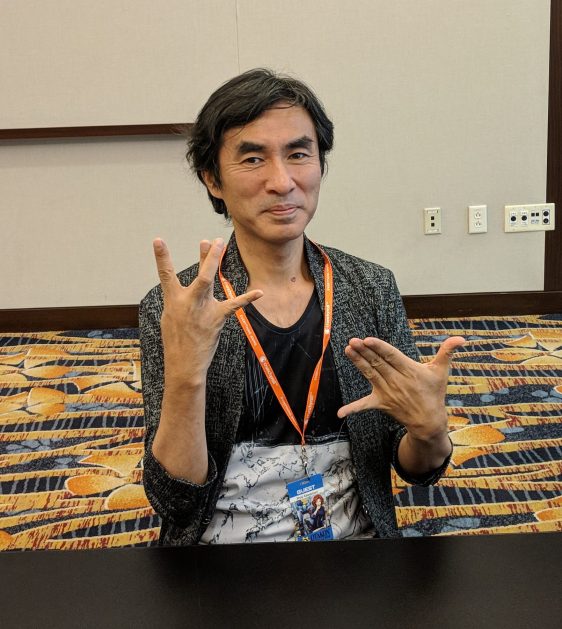

In my estimation, the biggest guest of Otakon 2018 was Kawamori Shoji, creator of Macross, Aquarion, AKB0048, Escaflowne, and even early Transformers designs such as Optimus Prime and Starscream.

Unlike other guests whose panels are generally moderated Q&A sessions, Kawamori actually gave two presentations at Otakon. The first was based on his TEDx Talk on originality and design, though I unfortunately wasn’t able to attend it. The second was a history of the Macross franchise from the perspective of its own father, which I’ll be detailing in this post. For more Kawamori content, check out my interview with him!

From Megaload to Macross

Kawamori spoke of his early days competing with his senpai Miyatake Kazutaka (of Space Battleship Yamato fame) on who could design a non-humanoid hero mecha first, only to get rejected by the toy company because humanoid robots were what sold. He told us the origin of Macross (originally Battle City Megaload in the early design phases) and how it was actually meant to be a joke on the sponsors—a bait-and-switch tactic for Kawamori and his friends to do what they really wanted—only for those same sponsors to get so onboard with the concept that it became a reality. Suddenly, all of the ridiculous things they threw in to mess with the concept of humanoid mecha (being the size of a city, transforming from a carrier, having a literal town inside, facing a giant enemy so that a robot that ridiculously big would be practical) were to be an actual part of the show. Naturally, he and his friends/fellow staff concluded the following: if you have a city, you need a singer. Thus, Lynn Mynmay.

While the combination of pop music and mecha is practically taken for granted today, Kawamori described how back when Super Dimensional Fortress Macross first aired, the fans were divided between those who loved Mynmay’s songs during combat, and those who thought the whole idea was nonsense. However, Kawamori embraced the idea of having music, not weapons, win the war. He mentioned how Director Ishiguro, despite liking the concept, thought it would be too unrealistic, but Kawamori pushed through with it anyway out of a sense of youthful bravado.

The story of Battle City Megaload was already somewhat familiar to me, so it surprised me that there was an even earlier prototype of sorts for Macross: a manga he made in high school along with his friends called Saishuu Senshi (“The Last Warrior”). This amateur manga featured a world where war had become so expensive that opposing sides would each send out one representative warrior in a powered suit to engage in a duel that would determine victory and failure. The enemy side’s scheme was that they started using unmanned weapons, going against the deal. His friends at the time would end up in college with him, and would become part of the staff for Macross, including defining 1980s character designer Mikimoto Haruhiko.

Designing the Valkyrie

Kawamori also elaborated on another major part of Macross: the VF-1 Valkyrie. According to him, that famous design actually came out of a long struggle with trying to make a transforming plane robot that didn’t have issues with maintaining good proportions in both robot and plane forms. The key breakthrough was when Kawamori looked at the F-14 Tomcat, and how the jet engines could become the arms (he previously thought the nose of the plane would have to be the arms).

From there, other aesthetic decisions, like having a simple and functional-looking head (unlike the popular designs of the past) as well as “feet” for the robot that each came in two sections, completed the look. Once he had the inspiration thanks to the F-14, actually designing the Valkyrie took about a week. Kawamori then pulled out not just an original-style Takatoku VF-1 Valkyrie toy to demonstrate its transformation, but also a pre-final prototype for a new 1:48 scale version of the same design due later this year, demonstrating its improved flexibility.

The Success of Macross Leads to New Perspectives

Macross was a hit, which led to Kawamori having his directorial debut at age 24 for the film Macross: Do You Remember Love? Kawamori mentioned how he came up with a lot of ideas for the film, like holograms during concerts, a vacuum-cleaning miniature robot, and clothes that change color. He expressed his surprise over the years seeing these farfetched concepts come to life.

Another result of Macross’s success was that Kawamori got to travel abroad, and the resulting trips actually dramatically changed his views on technology and culture. First, he spent time in the United States, where he more or less experienced the extremes of Macross’s aesthetic themes. He visited military bases and NASA space centers to watch shuttles launch, and he would go to Broadway musicals, sometimes even seeing as many as three plays in one day. He would often be up from 6am to 3am.

However, he started to feel the need to get away from that environment, which led to him traveling to China. With modern technology being sparse in areas such as Inner Mongolia, Kawamori recounted how he would see the children’s eyes light up whenever the television stopped working, and how their expressions while playing outside were like none he had ever seen. He then visited Nepal, where he encountered people who literally saw differently from him. Kawamori prides himself on having 20/10 vision, but even he could not see what his Nepalese guides could. They would wave at each other from enormous distances, holding conversations with each other while recognizing facial expressions that to him looked like mere specks.

While he still loves technology today, these experiences made him rethink his stance on technological progress being inherently good.

Macross 7, Macross Plus

Kawamori emphasized his desire to never do the same thing over and over, which is why 1987’s Macross: Flashback 2012 was an OVA, and not a TV series or a film. He kept getting requests to make another TV Macross, but he would refuse. The person who convinced him was a college underclassman who had got into the industry, the late producer Takanashi Minoru. Takanashi told him, “It’s been 10 years. You can go back to TV,” a reference to the statute of limitations for crimes in Japan.

Kawamori had one week to come up with a concept, and so he first thought of a singing pilot. But in order to add an extra twist, he turned the main character into a singing, non-fighting pilot. Thus, Nekki Basara was born.

Basara is a favorite character of Kawamori’s, but he thought that the old Macross fans would hate him for it, and he still had a love for mecha and planes himself. To appease his fans, he made Macross Plus. (It should be noted that according to Macross expert Renato, Kawamori refused to make Macross Plus if he couldn’t make Macross 7 as well).

As part of his research for Macross Plus, Kawamori and Itano Ichiro (of the famed “Itano circus”) flew real jets (with guidance) and had a dogfight with each other. The instructors sat next to them, but they got to use the controls. Itano is a rebel, so he ended up Itano doing everything the instructor told him not to, and kept blacking out from the g-forces. Itano said that every time he blacked out, he would hear voices from the distance saying his name. Kawamori asked him to recreate his blackout scene for Isamu’s.

Sharon Apple, the virtual idol from Macross Plus, is based on idea that making an anime is to some extent about emotional manipulation. The funniest thing was that, at the time, the staff said no one would go crazy for a virtual idol. Kawamori expressed that he never thought the concept would be embraced this quickly. It was also during this time that he was introduced to Yoko Kanno.

Macross, CG Graphics, and the Future

One of the dramas of real-life planes is when jet fuel runs out, but in the world of Macross, reaction engines means infinite power. That’s why Macross Zero is set in a time before that technology came to be. More generally, Macross Zero was about combining technology with the things he saw in China.

This was the start of his use of 3DCG in animation, which he started to use because he felt that 2D animation was limited in its ability to capture the proper camera angles for flying scenes. Macross Zero had a mix of 2D and 3D for action, and it was in Genesis of Aquarion that he tested out full 3DCG for combat. From there, Macross Frontier was to prove that the workload of a show could be divided between 3D for battles and 2D for characters. The Macross Frontier movies were where Kawamori finally figured out the ideal way to blend 3D and 2D together for scenes. Kawamori overall gave the impression that he sees new shows as opportunities to experiment.

One of the big changes in Macross Frontier was the use of two idols instead of one. Another decision was to make a male hero who’s even more beautiful than the idols. The Macross Frontier two-idol setup was popular and successful, but when the sponsors asked him to repeat the formula, he doubled down and made Walküre a team of idols as a separate division from the Windermere forces and the Delta Platoon.

Toward the end of the panel, Kawamori showed a lego prototype model for a transforming robot. Instead of two jet engines forming the legs, as has been the case with Valkyries, this robot has a single jet engine that turns into two legs. For Kawamori, it was the first new transformation system in quite a while. He then ended the panel by showing a trailer for Pandora, which comes out on Netflix this year.