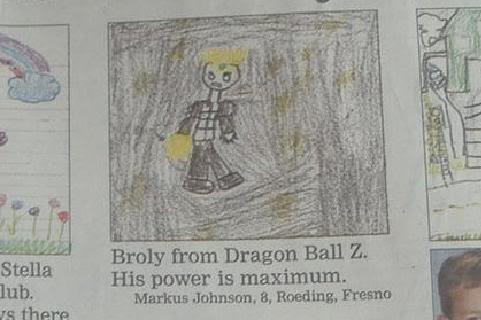

There’s an old and famous picture from a newspaper’s children’s section, where they asked kids, “If you could be a superhero, who would you be?” In response to this question, a boy named Markus answered, “Broly from Dragon Ball Z. His power is maximum.” But while people online have gotten lots of laughs from this innocent answer over the years, Markus’s words almost perfectly encapsulate the character of Broly, the Legendary Super Saiyan.

There’s an old and famous picture from a newspaper’s children’s section, where they asked kids, “If you could be a superhero, who would you be?” In response to this question, a boy named Markus answered, “Broly from Dragon Ball Z. His power is maximum.” But while people online have gotten lots of laughs from this innocent answer over the years, Markus’s words almost perfectly encapsulate the character of Broly, the Legendary Super Saiyan.

As an antagonist, Broly was always a one-dimensional character whose primary trait is being ridiculously and impressively powerful. To be fair, the way it’s portrayed in his appearances leaves a lasting impression, and has a clear, primal appeal to Dragon Ball Z fans. However, he’s ultimately a simplistic villain to be overcome by blasting him harder.

The character is also non-canon, appearing only in Dragon Ball Z anime films, which is why it’s rather significant that the creator of Dragon Ball himself, Toriyama Akira wrote the script for Dragon Ball Super: Broly. It not only means introducing Broly into the Dragon Ball universe proper, but also an opportunity to transform this flimsy rage machine into a fully fleshed character.

On a skeletal level, Super Broly is basically the same character: an instrument of revenge for his father, Paragus, against Vegeta (the son of the man he hates most, King Vegeta), who goes berserk and must be stopped by Son Goku and his allies. There are a couple of crucial changes, however.

First, in the original Broly film, Broly is shown as having an inadvertent deep-seated trauma caused by Goku when they were fellow infants, which causes him to wantonly attack Goku. This no longer is a thing, and when he and Goku fight as adults, they’re meeting for the first time. Second, in the new film, Broly is shown as being ridiculously strong and terrifying but ultimately innocent inside—as if his personality isn’t inherently that of a fighter.

Both are smart choices that lay the groundwork for making Broly a properly three-dimensional character. The Goku grudge used to come across as largely a flimsy device to get Broly in direct conflict with the hero of the story, and it kind of punks out Vegeta in the process. Without it, his background focuses more on him being unfairly raised by his own father to be a tool for revenge, and the different ways in which Goku, Vegeta, and Broly have been shaped by their upbringings and experiences. An extensive background story in the first half of the film highlights these differences.

That being said, I don’t want to make this film sound like a deep look into character psyches, as it’s mostly one gigantic fight scene full of the fast and frenetic combat Dragon Ball is known for. However, those crucial differences between Goku, Vegeta, and Broly come out even as they’re pummeling each other. Goku’s Earth-bases martial arts background, Vegeta’s elite Saiyan training, and Broly’s mostly unrefined berserker rage are all conveyed in the action, which does a lot of showing instead of telling somewhat reminiscent of Mad Max: Fury Road.

A few bits of welcome comedy alongside some new characters help keep Dragon Ball Super: Broly from feeling too heavy—a clear indication of Toriyama’s hand in the process. Overall, it ends up being a really solid film, and one that manages to give depth and meaning to a pure power fantasy character like Broly without taking away the strength that made him popular in the first place.