Welcome to the very first “Return to Genshiken,” a new series of posts where I revisit the very first Genshiken manga series. For those unfamiliar with Genshiken, it’s a series about a college otaku club and their daily lives. Originally concluding in 2006 before restarting in 2010 and finishing once again in 2016. A lot has changed about the world of the otaku, so I figured it’d be worth seeing how the series looks with a decade’s worth of hindsight.

Note that, unlike my chapter reviews for the second series, Genshiken Nidaime, I’m going to be looking at this volume by volume. I’ll be using the English release of Genshiken as well, for my own convenience. Also, I will be spoiling the entirety of Genshiken, both the old and the recent manga, so be warned.

Volume 1 Summary

Sasahara Kanji is starting as a freshman at Shiiou University, a college in the Tokyo area. He wants to join an otaku club, and after some false starts winds up in a club called the Society for the Study of Modern Visual Culture, or “Genshiken.” While he believes himself to be nowhere near as hardcore as the other club members, he discovers that he fits in well with the laid back atmosphere. As he learns the ropes about the otaku life, he’s also joined by other new members, including cosplayer Ohno Kanako, the usually handsome supernerd Kousaka Makoto, and Kousaka’s non-otaku girlfriend, Kasukabe Saki.

Back in Time

I must say, reading the first volume of Genshiken really is like going through a time warp. Not only is the visual style of the manga starkly different compared to how it ends up by Volume 21, but the aesthetic of the characters the Genshiken members themselves are obsessed with is a trip down memory lane. During this period, Genshiken makes references to series like To Heart and The King of Fighters, and the world of the otaku just seems…smaller somehow.

In one chapter, Tanaka is examining a garage kit of a cute girl model, and he remarks that female characters’ faces are getting rounder and cuter as of late. Keep in mind that this was back in 2002, before the K-On!‘s and the Bakemonogatari‘s of the world came along, the time of series like Star Ocean EX. Character designs like Lina Inverse from Slayers and Deedlit from Record of Lodoss War were still holding strong.

It’s also notable that the character profiles included between chapters bother to list each person’s “favorite fighting game character.” Fighting games still exist today, but it should be noted that they began to die out around 2003 before being revived in 2009 with the launch of Street Fighter IV. I think we’re catching the tail end of the fighting game craze.

Perhaps the most major difference between Genshiken and Nidaime is that the latter mainly focused on fairly contemporary references in order to emphasize that its values were more current. In contrast, the original Genshiken, by starting at a point where years and years of otaku history preceded it, draws from the previous decades in order to establish its characters and their preferences.

Memories Refreshed

There are a lot of things that happen in Volume 1 that I pretty much forgot, and a lot of things that, having recently finished Nidaime, stand out as likely reference points for the second series.

I did not remember that Sasahara joins Genshiken because Kohsaka scares him from the Manga Society. Given how close they become later on, it’s almost surprising to go back and see just how intimidating Kohsaka appears to Sasahara. It makes sense: Sasahara is a meek fellow, and he’s suddenly confronted with this idea that guys like him might populate the Manga Society. And just in general, most of the main cast of awkward nerds—Sasahara, Tanaka, Madarame, Kugayama—get really uncomfortable when it comes to regular-looking guys.

Going forward to Nidaime, it frames how Yajima feels upon entering the club all those years later. While Sasahara felt threatened by Kohsaka alone as a kind of living contradiction, Yajima sees herself as being practically surrounded by Kohsakas. Ohno is attractive. Ogiue is very attractive. Yoshitake’s surprisingly fashionable. Hato is Hato.

While I thought Madarame’s lamentations over all the sex talk in Chapter 125 was more of a general callback to how the club used to be, I find that it’s actually specifically in reference to the guys overhearing conversations from others about how much sex they have that can be found in Volume 1. If you just read Volumes 1 and 21 back-to-back, it is a stark contrast that the characters would go from freezing up and sweating nervously when some fellow talks about doing three girls in one day, to Sasahara and Tanaka both mentioning how they wish they had more sex with their girlfriends. Similarly, the way Madarame freezes when he sees Kohsaka and Saki kiss for the first time is possibly the long setup to the fact that he’s too passive to even get something started with Sue even after they start going out.

Another moment i had forgotten the exact details for was the very first Kujibiki Unbalance discussion we ever see. First, I had no idea that Kujibiki Unbalance is supposed to be a shounen manga, given its makeup. Second, the characters talk about the fact that the school in Kujibiki Unbalance is supposed to be a mix of various real schools—a self-aware nod to how Shiiou University is itself an amalgam of real schools.

Saki the “Time Bomb”

In this volume, the manga refers to Saki as a “time bomb” whose effects influence Genshiken in unforeseen ways. Looking back, this statement is more profound than I think even the author Kio could’ve imagined. She fundamentally changes a great deal about the club over time. It’s because of her that the members of Genshiken grow and evolve themselves as people, beyond the otaku stereotypes to varying degrees.

Outside of the possible exception of Sasahara, whose sister Keiko is very much the “gyaru” type, Saki is Genshiken’s biggest exposure to the “normal” world before the members start graduating. Because of her, Ohno goes from shy wallflower to mother figure for younger otaku. Madarame changes himself as he discovers his feelings for her. Ogiue learns to open up as well. She is a force for change in the club, and one might even argue that she’s the real protagonist of Genshiken, at least initially.

I also noticed that the presence of the real world outside of Saki is much more prevalent in Volume 1. The aforementioned bro talk situations happen. Saki herself gets hit on by guys looking for a quick fling. As the series continues, that realm fades from view until Saki is the primary example of it. And even then, Saki herself changes as she gets acclimated to being friends with otaku.

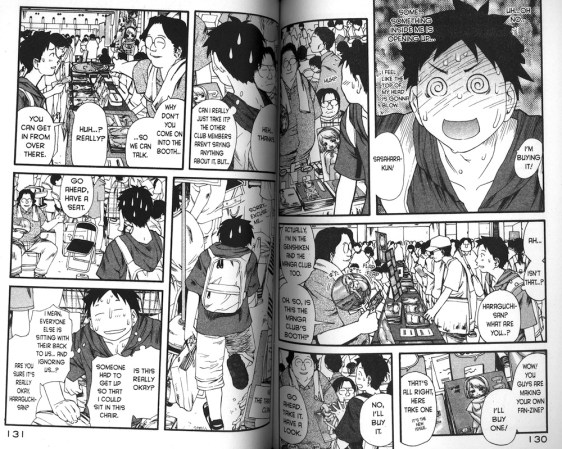

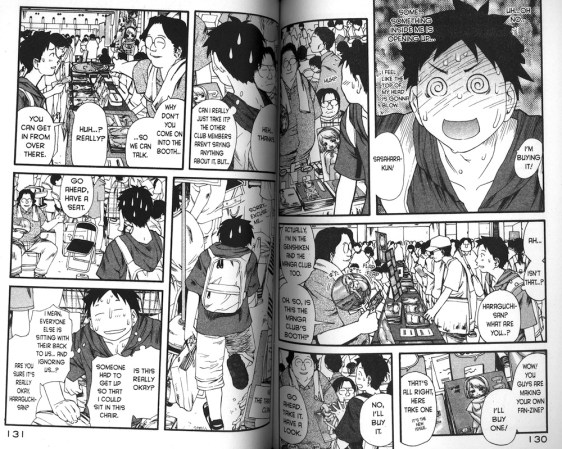

Comic Festival

I recall that, prior to my discovering Genshiken, my main exposure to the idea of “Comic Market” came from two anime: Comic Party and Nurse-Witch Komugi-chan. Suffice it to say, that’s kind of a strange combination. While Comic Party had a couple of Kuchiki-esque creepers, it was mostly portrayed as a fairly tame event. With Genshiken, however, seeing the final barrier of Sasahara’s shame come undone gives the full doujinshi-purchasing experience. In a way, doujin events are where you confront your true self, and see what values lie within. What are your real priorities? What fundamentally tickles your fancy? It’s a time for reflection.

Before Kuchiki, There Was Haraguchi

I think there’s a common feeling throughout Genshiken fandom that Kuchiki is an unnecessary element. Who wants to read about a guy with the absolute worst social skills, whose behavior is grating and downright pathetic? However, in Volume 1 Kuchiki has yet to appear. Instead, within early Genshiken exists the character of Haraguchi, and in many ways he provides an interesting contrast with Kuchiki.

Haraguchi is portrayed as an opportunist who likes to lord it over others. A member of all three otaku circles (Anime Society, Manga Society, Genshiken), it’s implied that each group barely tolerates him. Haraguchi works by making connections and ingratiating himself to those who “matter,” and he’s viewed as a leech who mooches off the success and passion of others. Haraguchi is that guy who gives orders without ever actually contributing, and the result is that no one in the universe likes him.

A similar dislike of Kuchiki is certainly prevalent, but for as much as can be said about Kuchiki’s flaws, being a manipulative person isn’t one of them. He’s obnoxious, lacks self control, has a tendency to give TMI, and perpetually irritating, but he’s also absolutely honest and upfront about who he is and what he enjoys. I think it’s ultimately why he’s allowed to stay with the club. Kuchiki is a man of innumerable faults, but he’s not a scumlord like Haraguchi.

Art in Progress

As I looked for the best image to include in this post, something hit me: the panel layout in Volume 1 is much less refined and elegant than what it would become. While there’s a nice sense of variation in terms of panel size, the composition isn’t as strong, the borders are rather rigid, and the pages don’t flow nearly as well. I’ve looked ahead a couple of volumes and it mostly seems the same, so I wonder if there’s a point at which it truly changes.

Actually, when looking just at the differences between chapters in Volume 1, the art style already begins moving towards the more familiar Genshiken style. As the series begins, the character designs are more similar to Kio’s previous works, and by the end of the volume they’re definitely getting softer. The difference between Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 is significant enough that I suspect they were drawn months apart. That’s what happened with Nidaime, where the pilot chapter still had the feel of Jigopuri.

Final Aside

I thought the portrayal of underage drinking was a Nidaime thing. Apparently not! It happens wit Kasukabe and Kohsaka right from the start.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

In 2013,

In 2013,