The manga Spotted Flower is more than just a story about a male otaku and his non-otaku wife. To fans of the author, Kio Shimoku, the series is also a thinly veiled alternate universe version of his most famous work, Genshiken. With nearly all of the characters in Spotted Flower having direct analogues in Genshiken, the manga is constantly nudging and winking at the audience. Recently, one of those nudges turned into more of an elbow to the solar plexus, and many assumptions about the series have gone out the window. A story seemingly about marital bliss (despite some ups and downs) has become a tale of adultery, and Genshiken fans are left reeling.

The manga Spotted Flower is more than just a story about a male otaku and his non-otaku wife. To fans of the author, Kio Shimoku, the series is also a thinly veiled alternate universe version of his most famous work, Genshiken. With nearly all of the characters in Spotted Flower having direct analogues in Genshiken, the manga is constantly nudging and winking at the audience. Recently, one of those nudges turned into more of an elbow to the solar plexus, and many assumptions about the series have gone out the window. A story seemingly about marital bliss (despite some ups and downs) has become a tale of adultery, and Genshiken fans are left reeling.

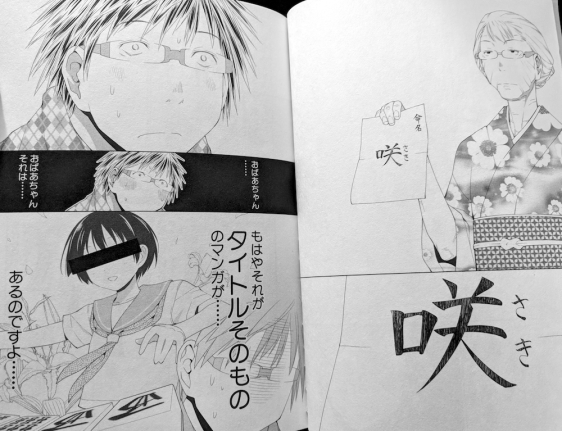

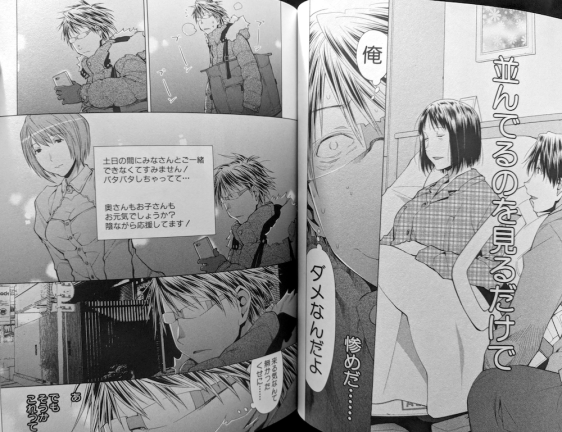

The buildup to the big moment occurs shortly after the birth of the husband and wife’s first child, who is named, appropriately, “Saki.” Visited by her ex-boyfriend, the ease with which she and her former lover banter back and forth drives the meek husband to wallow in quiet envy. In a moment of weakness, he ends up sleeping with an old mutual friend—one who’s female up top, male down below, and who still identifies as male—and cheats on his wife. Only, instead of doing the deed, he winds up on the receiving end.

Jealousy and Betrayal

It’s clear which Spotted Flower characters map to which Genshiken identities. The husband is uber nerd Madarame Harunobu, while his wife is the no-nonsense Kasukabe Saki. The ex-boyfriend is Kohsaka Makoto (who is Kasukabe’s actual boyfriend). The one night stand (?) is with Hato Kenjirou, the male BL fan who ends up falling in love with Madarame. Seeing all of these characters act so terribly to each other can feel like a betrayal, especially to fans of the popular Madarame-Kasukabe pairing. But the situation begs the question: where do the Genshiken versions end and the Spotted Flower ones begin?

Spotted Flower resembles fanfiction in the sense that, while it’s possible to enjoy it standalone, the work encourages and even to some extent assumes a certain degree of familiarity with the source material. What use is a story about Mikasa from Attack on Titan turning into a robot, if the reader doesn’t know how Mikasa is supposed to act normally? To that extent, I suspect that the controversial decision to make the husband an adulterer is part of stressing Spotted Flower as the space where all the things not possible in Genshiken become real. The very premise of the series is built on that idea—Kasukabe ultimately rejects Madarame because she loves Kohsaka.

If the husband does all the things Madarame didn’t or couldn’t do, then his poor decisions make sense. At one point in the second manga series, Genshiken Nidaime, Madarame comes close to sleeping with his friend’s little sister, Sasahara Keiko. As it turns out, Keiko is actually trying to cheat on her current boyfriend with Madarame, and her casual admission to this fact sends Madarame running for the hills. Madarame is unwilling to be an accomplice in another’s unfaithfulness, but the husband in Spotted Flower is not. Later in Nidaime, Madarame ends up alone with Hato in an awkward spot. Hearts racing, the two come close to having something happen, only for happenstance to deflate the tension. Madarame ends up rejecting Hato later, out of concern that Hato should be with someone better. The evening that goes nowhere in Genshiken certainly ends up somewhere in Spotted Flower.

What’s more, where Genshiken deals in relatively tame kinks and features mostly faithfully monogamous relationships where available (Keiko notwithstanding), Spotted Flower thrives on the unconventional. The not-Hato (hereafter referred to by his artist pen name Asaka Midori) is already in a physical relationship with his manager who’s the Spotted Flower version of Genshiken character Yajima. But rather than being upset or surprised, the manager was already well aware of Asaka’s desire for the husband. She even goes as far as to ask how it was giving anal sex to him. At another point, it’s implied that another character (a manga editor who maps to original Genshiken protagonist Sasahara) could maybe potentially be having threesomes with his girlfriend and her very touchy-feely American girl friend, but doesn’t. “Open relationships” seems to be the name of the game, which further emphasizes the Bizarro Universe-esque aspects of sexual relations in Spotted Flower relative to Genshiken.

Does this mean that Spotted Flower is reliant on Genshiken, or that the sense of betrayal on the part of readers would only come from Genshiken fans? Perhaps not, but the feelings are likely most intense from that established fanbase. However, I find it fascinating that, unlike fanfiction, which typically exists on a very clear line of what is “canon” and not, the fact that Spotted Flower is this very obvious Genshiken what-if with only the barest degree of plausible deniability makes that canon/non-canon distinction much blurrier. At the same time, it is fact that the Spotted Flower characters are definitely not the Genshiken ones, and not just the same characters in an alternate universe or timeline. They simply have too many different physical features that can’t be explained by the passage of time on account of the Spotted Flower characters being older. “Ogino-sensei” (Ogiue in Genshiken) has a different face structure. The blond American otaku behaves like the petite Sue but has a body like the tall, buxom Angela. In some cases, it’s not even clear who’s supposed to be who based on character design alone. Spotted Flower might be a “possible future” as both it and Genshiken like to put it, but it’s practically CLAMP’s manga, Wish—a series based on a JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure doujinshi of theirs with the names and designs altered into “original” characters. Only, for Kio, he’s his own source of inspiration.

Ogiue’s Counterpart: Ogino-sensei

The question as to how much Spotted Flower should speak for Genshiken is a tricky one. The characters of the former mirror the latter. Are they the true desire of the author, or simply a chance to tell different stories? Is it precisely because the characters are alternate versions that this can happen, or does that thread of possibility mean the two are tied together? I don’t believe there to be a true answer to these questions, simply because it really depends on individual readers’ relationships with both series. But it’s also curious that some of the characters and relationships are not as different as others. Ogino-sensei is still seeing her manga editor boyfriend, and their bond seems to have remained strong. The wife’s ex-boyfriend (not-Kohsaka) looks almost the same, except his hair is black instead of blond, and his bright-eyed gaze has been replaced with some kind of seeming cynicism or darkness. Maybe there are characters who can find the same happiness on the alternative route, and those who cannot.

A new character: Endou

How much Spotted Flower will continue to be self-parody remains to be seen. Volume 3 introduces wholly original characters in Asaka Midori’s editor, Endou, as well as her publisher. I wonder if this is the signal that the manga is on the verge of becoming its own entity.

We have Ogiue going to Comic Festival incognito, i.e. half a chapter devoted to showcasing Ogiue’s mix of anger towards others, anger at herself, and the sense that she just really want friends but is her own worst enemy. As she stomps through Tokyo Big Sight in her winter coat and high school-era glasses, a snarly pout adorning her face, you can see her giving into her basest desires, mirroring Sasahara’s first voyage to ComiFes (though this is certainly not Ogiue’s first rodeo). When Ogiue’s hovering around the rest of the club, the lonely look she gives as they laugh over in the distance is almost heartbreaking. The subsequent silliness of her bumping into Ohno and having her doujinshi spill out of her bag for all the world to see is dramady at its finest. In other words, Genshiken.

We have Ogiue going to Comic Festival incognito, i.e. half a chapter devoted to showcasing Ogiue’s mix of anger towards others, anger at herself, and the sense that she just really want friends but is her own worst enemy. As she stomps through Tokyo Big Sight in her winter coat and high school-era glasses, a snarly pout adorning her face, you can see her giving into her basest desires, mirroring Sasahara’s first voyage to ComiFes (though this is certainly not Ogiue’s first rodeo). When Ogiue’s hovering around the rest of the club, the lonely look she gives as they laugh over in the distance is almost heartbreaking. The subsequent silliness of her bumping into Ohno and having her doujinshi spill out of her bag for all the world to see is dramady at its finest. In other words, Genshiken.

At first glance, Nikaido Yuzu in Aikatsu Stars! is not an especially unique character. She’s an energetic, bubbly character in a show filled with energetic and bubbly characters, in a genre (idol anime) conducive to energetic and bubbly characters. One or way or another, however, she comes to stand out over time, especially with the slight shift in her role between seasons from kouhai to senpai.

At first glance, Nikaido Yuzu in Aikatsu Stars! is not an especially unique character. She’s an energetic, bubbly character in a show filled with energetic and bubbly characters, in a genre (idol anime) conducive to energetic and bubbly characters. One or way or another, however, she comes to stand out over time, especially with the slight shift in her role between seasons from kouhai to senpai.