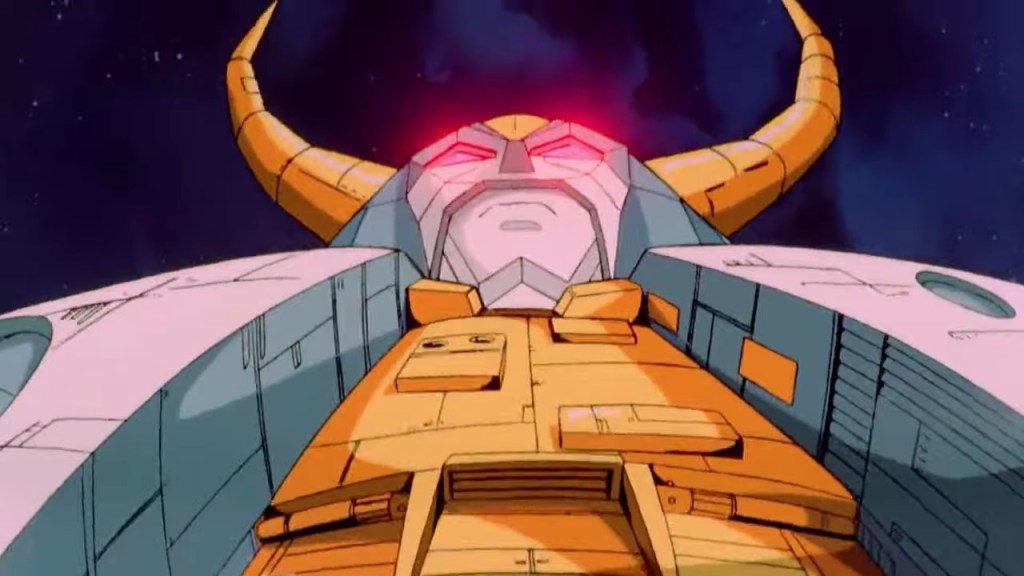

The latest Soul of Chogokin figure was announced last month, and it’s Daitetsujin 17 (pronounced “One-Seven”) from the 1970s tokusatsu series by the same name. It was created by the very father of tokusatsu, Ishinomori Shotaro, and features the classic “little kid remote-controlling” giant robot motif that began with Tetsujin 28. Prior to its release, I never watched any Daitetsujin 17, but I decided to check out the first episode, and what I noticed is that the promo images for the SoC version really capture how the toy is designed with a kind of live-action clunkiness seen in the original program itself.

There’s no doubt that this is highly intentional, as the Soul of Chogokin line is famous for trying to get as close to “show-accurate” as possible. Japanese toy reviewer wotafa stated in his look at the POSE+ METAL Gaogaigar that one of the big things differentiating it from the earlier SoC release was that the latter is more faithful to the anime, while the former looks like “Gaogaigar came back from studying abroad in America.” But in contrast to the myriad anime-derived Soul of Chogokin figures, adapting tokusatsu giant robots like Daitetsujin 17 seems to present another sort of challenge.

Whereas the anime robots have to reconcile the contradictions between the (mostly) two-dimensional drawings with the three-dimensional realities of the toys themselves, a different conflict is in play. Tokusatsu shows typically have their mecha appear in two different ways: as a model for transforming and such, and as a costume for a suit actor to fight in. A figure whose goal is to bring the source material to life has to balance these two dominating visuals, and from what I can tell, Daitetsujin 17 looks like it succeeds on that front.

But Daitetsujin 17 is not the only live-action robot to get the SoC treatment, and so I started looking at past instances to see if that characteristic tokusatsu-ness is still present. What I found is that, while not as strongly flavored as Daitetsujin 17, that feel is still present to varying degrees.

The recently released Daileon from Juspion comes from a different era than Daitetsujin 17, but the premium it places on poseability goes to show just how important it is to capture that “guy-in-a-suit” element of the show. Comparing the 3DCG trailer they released to the live-action footage, you can see how much emphasis was put on making sure Daileon could strike all its signature poses, as if to say the very acting of posing defines the feel of Juspion as a whole:

A more popular SoC figure, at least among English-speaking countries, is the Megazord (or Daizyujin) from Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers. This one looks more like it emphasizes a cool, stocky appearance that’s a bit removed from how the Megazord usually looks in motion.

However, when compared to a similar figure released around the same time—Voltron (aka Golion)—the contrast in proportions between the two really drive home how the Megazord was made with different considerations in mind. It’s notable that the SoC Voltron has lankier proportions than its original toy from the 1980s to be more in line with its iconic pose from the anime’s opening.

This trend continues all the way back, whether it’s Leopardon from Toei’s Spider-Man, Battle Fever Robo from Battle Fever J, or King Joe from Ultra Seven.

The Daitetsujin 17 figure seems to most greatly embody the concept of tokusatsu-faithfulness, and I think that speaks to how far the Soul of Chogokin line has come. Every year, it seems to get more and more impressive, and I have to wonder what they’ll tackle next. Although the Daitetsujin 17 and many of the tokusatsu-based figures aren’t my priority, I find I can appreciate the lengths they’ll go to making the biggest nostalgia bombs possible.