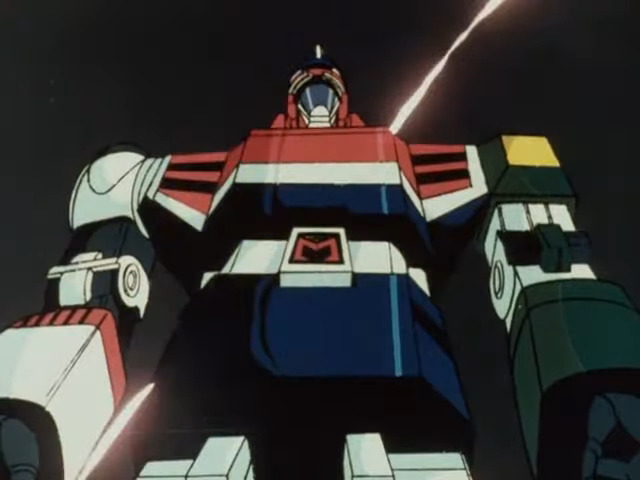

Sometimes I watch an anime where I think, “Man, that would make one hell of a video game.” Id: Invaded is one such title. It’s a kind of Inception meets Minority Report, where the main character’s ability to jump into a serial killer’s vague subconscious sets up the story as a series of “puzzles” that bring a different flavor to the idea of a “psychological profile.”

The basic premise of ID: Invaded is that an advanced form of technology allows the police in Japan to pick up psychic traces of a serial killer’s mind, and to send someone in to try and figure out the culprit’s identity. This task is given to Narihisago Akihito, who enters these “id wells” and transforms into an alternate persona known as the brilliant detective Sakaido. The major caveats of this process are that entering these mindscapes means you do not have memories of your real self, losing your life inside feels as bad as actual death, and you cannot retain what you’ve experienced in between sessions. It’s up to the officers on the outside to process the information they receive from Narihisago, and to make moves in reality. Underlying all this is Narihisago’s own traumatic past and the ways he attempts to atone by working through this bizarre system.

What got me hooked onto ID: Invaded is that the mystery is not just the identity of a given serial killer, but trying to figure out how their mind works from within without any direct signs as to who they are. The limitations of the system, as described above, are like a crueler version of a Rogue-like, where you don’t just lose all your material progress but the things you learned in the previous session. I also like that it involves having two tracks working side by side: the “subconscious game-like world” and the world of flesh-and-blood detectives. The character of Hondomachi, a young rookie on force, grows in interesting ways as she increasingly toes the line between the two realms.

But fantastical elements or not, a mystery series comes down to how well it sticks the landing. I In the case of ID: Invaded, I think it does adequately but there are some downsides. For one, I think the series escalates a little too quickly from one storyline to the next, and the big case that defines the later episodes makes it hard to imagine what could top it in the potential sequel that seems to be implied by the end. Also, the second half starts to break some of the rules established in the first half as another way to show how the stakes have gotten higher, but it stymies that excellent puzzle game-like quality established early on. The rules of detective fiction aren’t iron-clad, and I wouldn’t mind it down the road, but it just feels like it came too soon.

Still, the characters, the basic conception, and the overall story of ID: Invaded are excellent. I’d love to see more; I just don’t quite know how they’re going to keep the “boundaries” intact enough to let the logical limitations presented by the narrative shine through stronger than before.